Someone We Watched: Mike Ott’s People, Places and Things

Each year, the Film Independent Spirit Awards give the Someone to Watch Award to an emerging filmmaker of singular vision. In this column, film critic David Bax revisits some of the grant’s recipients to see how their work and careers have continued to develop.

***

Though its protagonist is played by a standup comic (the very funny Atsuko Okatsuka), who has a cowriting credit on the film, Mike Ott’s Littlerock (which won him the Someone to Watch award in February of 2011) isn’t a comedy. Sure, its loose plot—about a young Japanese woman stranded in a tiny, poor, desert-adjacent community in the deep, sparse, inland part of Los Angeles County—may have the ingredients for a classic fish-out-of-water tale. And there may be more than enough awkward situations to form a comedy of discomfort.

But laughs aren’t on Ott’s mind. Those awkward encounters contain more potential danger than humor. When she finds herself, say, a bystander to a threatening loan shark shakedown in a small motel room, we worry for Atsuko (it’s also the character’s name) because she’s a stranger in a place where crime and violence seem always to be lurking in the film’s crepuscular shadows.

We might be especially given to worry because of her slightness and attendant soft-spoken demeanor. But that’s a projection based on assumptions about her supposed meekness not supported by the evidence of her actions. After a point, it should be noted, she’s in this situation of her own volition. Her brother Rintaro (Rintaro Sawamoto) has fixed their broken-down car but she has decided to let him continue the next portion of their trip without her while she remains in the town of Littlerock on her own.

Atsuko’s reasons for this choice are not elucidated and, therefore, left for us to piece together by observation (Littlerock is calculatedly stingy with subtitles for the Japanese dialogue.) Rintaro seems intent on edification as a part of this trip; he’s eager to visit Manzanar, for instance. Atsuko, though, seems interested in a different, more inward-looking sort of discovery. With her brother gone, she’s alone in a place that might as well be another planet, separated from everything about her life that previously existed except for her mind and body. It’s an opportunity to get to know herself or, more precisely, her self.

Rintaro is less inquisitive about his own identity. He states with conviction that he and Atsuko don’t belong in Littlerock. And the film leaves room for the possibility that he may be right. The mere mention of Manzanar serves to remind us of what it can look like to be “accepted” into American society. But that’s not what Atsuko wants. She’s not seeking the approval of her new friends, like the crush-stricken, suffocating Cory (Cory Zacharia). The only acceptance she’s looking for is her own.

Ott’s collaborations with Okatsuka, Zacharia and others who appear here began before Littlerock and continued after. In the five years following its release, he made three more films, all with place names from the same vicinity for titles, with members of his company playing people inspired by themselves; Pearblossom Hwy, Lake Los Angeles and Lancaster, CA. That last one, the short film, is a documentary. But the distinction between fiction and nonfiction sometimes seems to be immaterial to Ott. He wants people to reveal themselves on camera. If pretending to be someone else is the best way to accomplish that, so be it.

Which brings us to 2016’s Actor Martinez, Ott’s most recent feature length film as of this writing. Actor Martinez presents first as a documentary. Ott has left the Lancaster/Palmdale area and, along with co-director Nathan Silver (Uncertain Terms, Stinking Heaven), made his way to Denver at the apparent behest of aspiring actor/producer/promoter Arthur Martinez to make a film about him. We watch him cycle through the collection of side hustles and never ending networking that seems to make up his life. Later, we see him concocting potential scenarios to act out with Ott’s and Silver’s help.

And so again we’ve got an onscreen presence appearing as themselves or a version of themselves, participating in the crafting of the film. And, like Atsuko, Arthur seems keen to learn about himself. After all, he’s gone so far as to enlist a documentary crew to undertake a deep examination of him and see what they can find.

Where Atsuko is quiet, observant and even passive, though, Arthur is frantic and loquacious. As he comes into focus (or fails to), it grows more and more apparent that revealing the truth about himself—or anything at all beneath the surface—is the last thing he wants to do. His state of constant motion and chatter is an endless ploy to keep self-awareness at bay. He doesn’t want to learn who he is; he wants to tell us who we would like us to think he is.

Still, Ott’s methods, his patient curiosity, work. Arthur’s insecurities come through in his pickiness about how he’s shown but, more importantly, a picture of his inner sweetness and thoughtfulness starts to form. To achieve this, Ott and Silver (who both appear as themselves or characters or whatever you want to call it in this amorphous project) have to become the bad guys, callously pushing both Arthur and Lindsay Burdge, the actor hired to portray Arthur’s girlfriend, into uncomfortable situations.

There is, admittedly, a falseness here. It’s obvious that this behavior is a put-on for the movie. But that only speaks further to Ott’s dedication. He’s so selfless a filmmaker that he’s willing to sacrifice his own persona to help illuminate the best parts of Arthur’s.

It’s been the default lens through which we view filmmaking for so long that the auteur theory has become something of a self-fulfilling prophecy. Littlerock and Actor Martinez are persuasive reminders that there are other ways to both make and discuss movies. Ott’s penchant for collaboration makes for a cinema that is not only multifaceted but deeply humanistic.

Other nominees: Like Ott, Dog Sweat director Hossein Keshavarz’ most recent feature is from 2016, Eugenia and John, but he’s also worked behind the scenes on films like his sister Maryam Keshavarz’ Circumstance and Amber Tamblyn’s terrific directorial debut Paint It Black; as a film director, Laurel Nakadate’s only follow-up to The Wolf Knife is a short film from 2014 called The Miraculous but she has continued to work to much acclaim in photography and other media.

Film Independent promotes unique independent voices, providing a wide variety of resources to help filmmakers create and advance new work. Become a Member of Film Independent here.

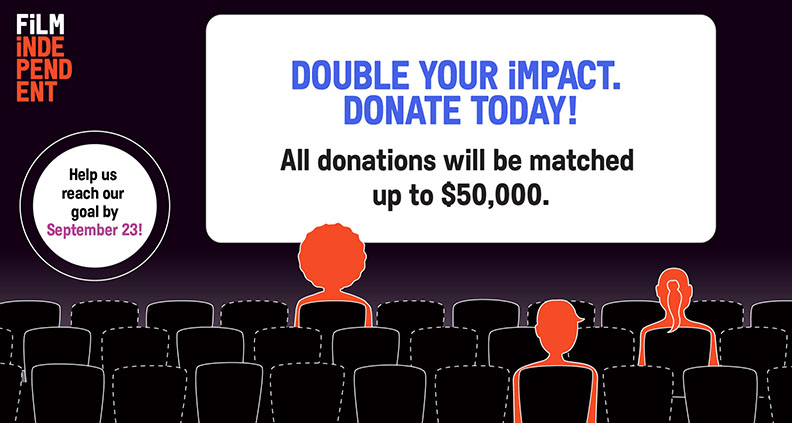

If you are in a position to support our efforts, please make a donation. Your impact will double, dollar-for-dollar, with the generosity of our long-standing Arts Circle Member Susan Murdy. All donations made to Film Independent before September 23 will be matched up to $50,000.

Follow Film Independent…

(Header: Littlerock)