OpEd: Legacy and Power Disrupted: A Case for ‘Birth of a Nation’ (Repost)

Recently LA Film Festival Director of Programming Roya Rastegar was invited by NBC News to pen an OpEd about the controversial release of Nate Parker’s new historical drama Birth of a Nation. The article, which ran on NBC Friday, October 7 is reposted here with permission.

***

In August, I was caught in a series of traps every time I engaged a discussion around the reported rape charges from twenty years earlier that Nate Parker had been acquitted of by a near all-white jury. I entangled myself in the details, but even after 700 pages of courtroom transcripts, I still could not “know” what happened.

What I do know, as human being and as a survivor, is that rape is wrong, no matter the victim or the perpetrator’s race, sexuality, or gender. I also know that two crucial points needed to be added to any discussion of Nate Parker’s directorial debut, The Birth of a Nation: 1. Sexual violence has a racial context, one that has been defined not only by the history of our country, but also the history of cinema. 2. Black directors in the film industry are particularly vulnerable to character valuations that threaten future filmmaking prospects. And we need Black storytellers now more than ever.

D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915) is the very first feature-length film ever made, and arguably the most damaging precedent for how Black people are represented in film and television. In the early 1900’s, movies were short reel loops designed to amuse and inspire, akin to Snapchat and Vine. So when audiences saw a feature-length film on the big screen, it felt so real, people consumed it like truth.

Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation represents white people in a state of utter panic in the aftermath of slavery’s abolition, and the economic and social shifts required for Black people to earn money, own property, and pursue education. In a seminal moment of Griffith’s film, a white woman throws herself off of a cliff rather than submit to the sexual advances of a Black man. This film cements the myth of Black men as rapists, and inspired white men to lynch Black men in defense of white women. President Woodrow Wilson said the film was “like writing history with lightning, and my only regret is that it is all so terribly true.”

Inspiring the rebirth of the KKK after almost thirty years of inactivity, Griffith’s film was used as an actual recruiting tool. The KKK never burned crosses before The Birth of a Nation, but the new KKK burned crosses – just like in the film. Life imitated art, for generations. The fatalities endure. “You rape our women, and you’re taking over our country,” said a young white man before murdering nine Black people in a South Carolina church exactly one hundred years later, on June 17, 2015.

Films and television have programmed fear and panic into the psyche of white and non-white viewers for generations. The greatest cultural dilemma of our time is how to train American society to unlearn a fear of Black people that has been cultivated and evolved through cinematic storytelling.

An internet search for The Birth of a Nation now turns up Nate Parker’s film: the ultimate interruption in Griffith’s legacy. The very existence of Parker’s film fundamentally interrupts the story that Griffith is trying to tell about Black people and their relationship to this nation.

“White men lynched negroes knowing them to be their sons. White women watched men being lynched knowing them to be their lovers.” – James Baldwin

Sexual violence and consent carry racial legacies. Centuries of sexual violence against people of color have been enabled by a legal system that is designed to protect white people and property, not Black people or their innocence.

In 1892, Ida B. Wells’ published research documenting that a quarter of Black men were lynched based on (largely false) rape allegations from white women. Wells research notes that white women were consistently pressured to renounce their relationship with Black men after being confronted by white men – and the law. Anti-miscegenation laws were in full effect until the 1967 Supreme Court decision of Loving v. Virginia.

As a scene in Parker’s film Birth of a Nation makes clear – during slavery, consent was not an option for Black women who were considered property and whose children, even when those children were the sons of slave owners, become the labor supply this country has been built on.

The imposed shame of interracial sex and love does not just vanish decades later. It evolves. From the Scottsboro Boys in 1931 to the Central Park Five in 1989, there are numerous cases and a considerable body of research that show black men are disproportionally wrongly convicted of sexual assault against white women. Meanwhile, Black women report rape at less than half the rate that white women do, often because of a lack of trust in the legal system and law enforcement. Mainstream coverage of sexual assaults against Black women is sorely lacking, as in the case of Daniel Holtzclaw.

Art is not separate from its maker, except when it pertains to white directors, who not only have their art celebrated for art’s sake – they also gain impunity through it. Alfred Hitchock, Roman Polanski, and Woody Allen, a few examples among many, are considered among the greatest directors of all time, and their sexual assaults are well documented. Hitchock tortured, sexually harassed, and assaulted his actresses. Roman Polanski was charged with sodomizing a 13 year old and hasn’t returned to the US in 30 years to avoid prison. But he still has four Oscar nominations, two Golden Globes, and two BAFTAs. Several years after Woody Allen was acquitted of molesting one of his adopted daughters, he went on to marry his stepdaughter. Yet, Allen is still given multi-million dollar films year after year, racking up four Oscars, 19 nominations, and two Golden Globes. The firestorm around these assaults only further iconizes these directors as “personalities,” offering a colorful footnote in the archives that celebrate their work into old age.

So why haven’t audiences stood up en mass in solidarity for the white female victims that Polanski, Allen, and Hitchcock, among so many others, have assaulted? Why haven’t the sustained feminist movements against Polanski had an impact on financiers and studio executives willing to work with him? To confront white men about sexual assault would require media outlets, actors and actresses, industry professionals to risk their access to that power. (When The Hollywood Reporter published an op-ed from Dylan Farrow’s brother about Allen’s molestation of his underage sister, THR’s reporters were blacklisted from Allen’s press junkets.)

We do not call for a boycott of films by white men because we know this would have no impact on their careers or awards. White directors are not remembered for their sexual assault. They are remembered for their stories. Those stories define our culture, our desires and fears. Those stories are the stuff history is made of. That is real power.

Nate Parker is not entitled to that power. We as the audience have the power to make or break not only Nate Parker’s film, but his entire directorial career. Even though Parker was acquitted of all charges when he was a teenager, he and his career remain vulnerable precisely because he is Black.

The $17.5 million sale of Birth of a Nation at the Sundance Film Festival is unfortunately not an indication that the film industry suddenly recognized the value and power of films by Black directors. The past two years, the Academy has come under fire for not recognizing Black talent at the Oscars, particularly after F. Gary Gray’s Straight Outta Compton and Ava DuVernay’s Selma, which despite seeming undeniable in their Oscar worthiness, were both passed over.

At the nexus of two powerful social media campaigns, #BlackLivesMatter and #OscarsSoWhite, Birth of a Nation sparked a heated and contentious bidding war because the film represented a surefire Oscar win.

As a film curator, I know #OscarsSoWhite is not because directors of color are rare. Rather, it is because Black creative life is untenable. Black filmmakers must embody a respectability that white people can feel good about and people of color can feel proud of. Infractions are not a set back, they are a death sentence.

If Nate Parker’s film fails, Birth of a Nation may become a cautionary tale to be held against other Black directors. Films by Black directors will be evaluated not on the stories they tell, but on the person they are made by. Buyers and financiers will know for the investment in a Black film to be worth it, the Black filmmaker him/herself must be infallible. This defeating imposition of Black respectability can only reaffirm Hollywood’s discriminatory hiring practices and the Academy’s homogeneity. And if the Oscars stay white, film distributors will think twice before buying another film by a Black director at a film festival.

But now more than ever, we need Black leaders who can change the narrative. Our racial history is a maze that has left us with a mess of violence, fear, and degradation. Black filmmakers can guide us through this history as we figure out the state of America today.

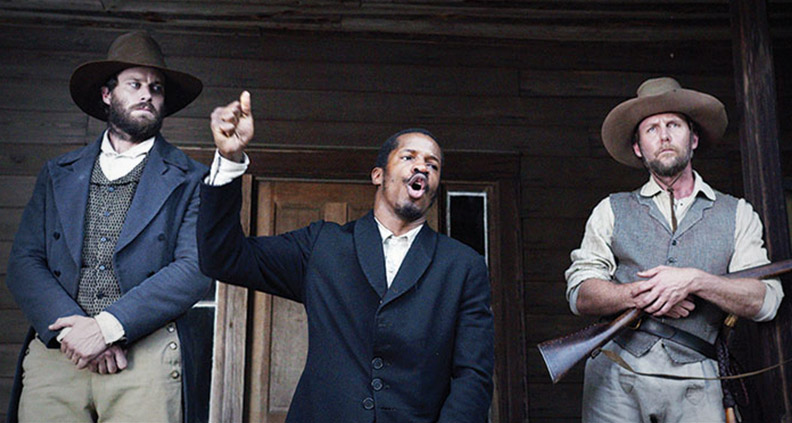

Nate Parker’s Birth of a Nation invokes a world in which we can immerse ourselves in Nat Turner’s story – a story of Black agency, organizing, and self-determination. Slavery was not abolished because of the grace of a white liberator or the burden of white guilt, as is so often represented in films about slavery. Black people strategized for freedom, fighting to change a system that seemed impossible to change.

Threatened everyday with the promise of an America made great again, and the continued murders of Black people by the police, seeing Birth of a Nation is necessary to rewire our minds so we can conceive of another kind of history, that can compel us towards a more just future.