Old v. New: Artificial Intelligence in ‘Blade Runner’ and ‘Autómata’

In our regular feature Old v. New, Kimberly Marcela Duron compares a newer independent release with an older classic to see what similarities they share, how they diverge and hear what the conversation between the two films says about filmmaking as the art form continues to innovate and evolve.

THIS MONTH: BLADE RUNNER (1982) V. AUTÓMATA (2014)

The history of Ridley Scott’s 1982 cult classic Blade Runner is a controversial one—especially considering the many different versions of the film that had continued to trickle out into the marketplace over the last 20+ years. Creatively speaking, the 2007 “Final Cut” version is Scott’s preferred iteration, with key plot and tonal changes made as well as enhancements to the film’s use of technology. But whether we’re talking about the original, studio-approved happy-ending theatrical version or the subsequent revamped, plot-twist versions, the film has become an icon in the world of sci-fi. As such, Blade Runner has served as the inspiration for countless films, from its neo-noir dystopian aesthetic to its interpretation of the conflict between man and machine; commercial films like The Terminator, I, Robot and Her have all depicted worlds in which humans and artificial intelligence engage complicated relationships.

One such film that bears a striking resemblance to Blade Runner is the 2014 Spanish-Bulgarian science fiction film Autómata. Directed by Gabe Ibáñez, the film takes place in the year 2044, after events that have left Earth with irreversible environmental damage and reduced to a fraction of its population. To help humans cope with this new reality, a corporation called ROC has developed humanoid robots called “Pilgrims” who have been put to use for manual labor like construction or domestic help. Enter ROC insurance investigator Jacq Vaucan (Antonio Banderas), assigned to a case where a cop shot a robot he claimed was modifying itself illegally. But while the two films share a similar premise, their interpretations of classic sci-fi conventions, world building approach and conversations around humanity and artificial intelligence make each film unique.

As in most films centered on robotics, the machines in each of the two films have presets created by man to prevent exactly what ends up eventually happening: robots becoming capable of making their own decisions, and thus, rebelling against human orders. In the case of Blade Runner, this preset is defined as a four-year lifespan for the film’s “Replicant” lifeforms. In Autómata, there are two unalterable protocols: no robot can harm any form of life, and no robot can repair or alter another robot. These are direct references to “The Three Laws of Robotics”—a set of rules made by the influential science fiction writer Isaac Asimov and used in many subsequent works of science fiction.

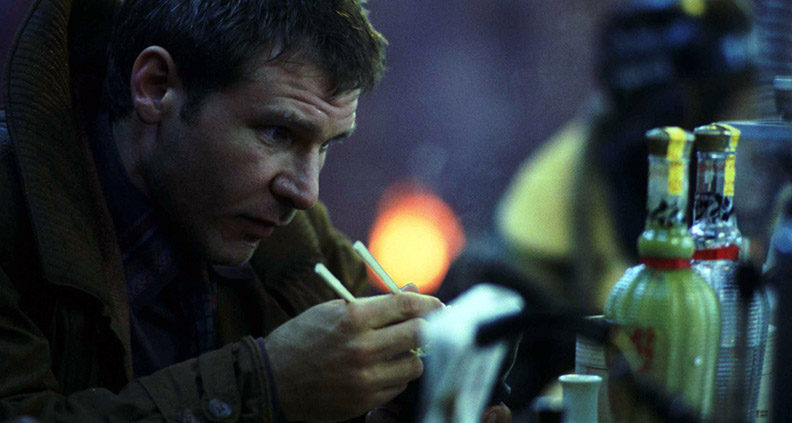

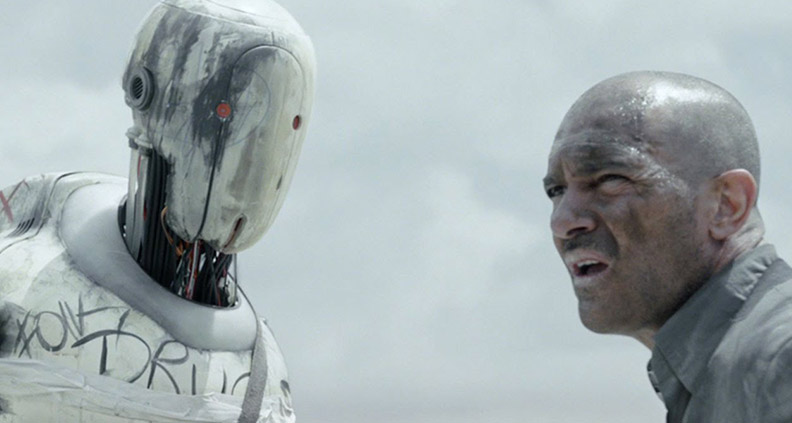

Another interesting take is the physical appearance of the AI systems. In Blade Runner the Replicants are designed to be superhuman, with superior strength—perfect for being at the forefront of the off-world colony wars. In Autómata, “Pilgrims”, though imitating basic human anatomy, are designed to function more like computers, complete with a processor where their brain would normally be. Naturally, it seems easier to empathize with Replicants, whose facial expressions can convey emotions like pain, fear, longing, etc. They become so human, that futuristic gumshoe Deckard (Harrison Ford) ends up falling in love with a femme fatale replicant called Rachael (Sean Young). But even in Ibáñez’s film, the lack of an epidermal layer doesn’t stop from Vaucan from ultimately accepting the robots’ “desire” to detach themselves from human use.

One of the things that usually makes or breaks a sci-fi film’s credibility is whether or not the world in which the story takes place is truly fleshed out. Blade Runner first situates itself as a neo-noir, with low-key lighting and smoky interiors, full of hard drinking and disgruntled cops whose cluttered desks are bathed in shadow. There’s perpetual rain—days that look like nights in a dystopian Los Angeles where high-tech billboards and rubble in the streets are both equally abundant. Each scene has costumes, props and sets that are so detailed and layered that the world truly comes alive and enhances (rather than distract) from the story.

The same can be said about Autómata, set in a world troubled by desertification. The city is enclosed by a wall, in which the primary communication methods are pagers and fax machines. It’s a weird detail, but in the world we are introduced to telecommunications have been disrupted by environmental phenomena, with heaps of computers sitting in garbage dumps outside of the city—a justified detail in the film’s overall design. Autómata is not a neo-noir stylistically, but we still see Vaucan as a burnt-out, morally ambiguous investigator who takes on a dangerous case and embarks on an existential journey. There are other nods in the film to its ‘80s predecessor, like eerie hologram advertisements that play on a loop, the symphony of steam, rain and neon in an urban setting, the inevitable sexualization of robots and its protagonists’ mud-brown raincoats that hang almost as heavy as their despair.

The major point of departure between the two films is their conversation about man vs. machine. In Blade Runner, the ominous Tyrell Corporation has artificially created a man in man’s image—essentially playing God, but taking things a step further to enhance qualities like strength and even implanting memories to create a more realistic sense of life. It’s clear with the four-year lifespan that, for the Replicants’ creators, artificial intelligence had more to do with a fantasy about how humans could be someday. Autómata takes a different approach. The ROC corporation has created humanoids for have a more specific purpose—to serve humans. Replicants have files on their history, but Pilgrims have serial numbers and two unalterable protocols.

The latter is an example of the need for humans to control technology and the fear that the smarter we make it, the less it will need us. And just as with Deckard and the Tyrell Corp., Vaucan discovers that the robot rebellion is the expression of a species (albeit man-made) striving to evolve. That’s the beauty of these films; when they pose a difficult question in their imaginary world, they allow us to make our own interpretation in the real world.

To learn more about Film Independent, subscribe to our YouTube channel or follow us on Twitter and Facebook. You can catch up with the rest of our blog here. To learn how to become a Member of Film Independent, just click here.