Making a Documentary Is Like Living Life: Nonfiction Filmmakers Gather for ‘Coffee Talks’

Moderated by Ondi Timoner (Dig!, We Live In Public)—the only two-time recipient of the Sundance Grand Jury Prize for documentary filmmaking—the Documentary panel returned to the LA Film Festival Coffee Talks series (located at the historic Culver Hotel in Culver City) on Sunday, June 5 for the first time in years.

The panel kicked off with a discussion of the challenges nonfiction filmmakers face when trying to keep their professional and personal life separate.

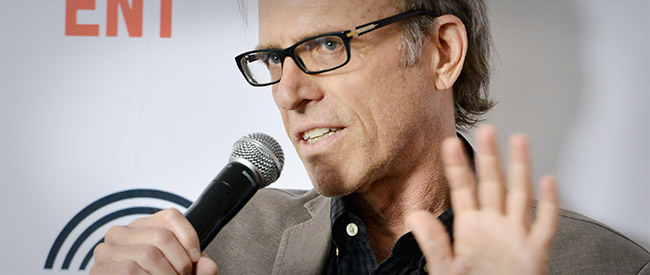

“Your [documentary] subjects become part of your family,” said panelist Kirby Dick (The Invisible War, The Hunting Ground). “In some ways, you’re living your life as you’re making your documentary because you get so close to your subjects.”

Dick’s latest project, The Hunting Ground, shines the spotlight on the immensely prevalent sexual assault culture on college campuses across the nation. The film’s original song “Til It Happens To You” made a splash at this year’s Academy Awards, as Lady Gaga performed a rendition after a moving speech by Vice President Joe Biden, aimed at bringing attention to the epidemic. Dick was immensely touched by Gaga’s contribution to the film. “With sexual assaults, it’s almost always about the pain. [The performance] was about the pain but it was also about the triumph. That’s a real tribute to Lady Gaga,” he said.

Throughout the one-hour discussion, the panel—which also included Lucy Walker (The Crash Reel, Waste Land)—touched on a variety of subjects, including:

How do you remain objective with “family” during editing?

The process of completing a long-form documentary project can take several years. After spending that amount of time with the subjects, remaining objective during editing can be a challenge. Timoner was very candid about the predicament—especially when it comes to dealing with darker subjects: “I’ve come up against this wall where I feel like I can’t finish a movie unless I find the love for my subjects, no matter what. If I don’t love the subject, then I feel like then the audience could never have compassion, could never love that subject.”

Walker added, “Sometimes you’re with people in the most intense moments of their life. You’re with people when they get the news that they’re going to die, when they’re dying. You wind up being the person accompanying them, and documenting them, but also just with them.” So the idea of objectivity is, quite simply, both illusive and elusive.

Dick, on the other hand, doesn’t dwell on objectivity as much: “There’s a difference between the character you’re cutting and the subject that you know, and you keep that different. You know that what you’re putting together is not necessarily the entire person. It’s the character in a project you’re building.”

Everyone would do it if it were easy

When lamenting the challenges unique to documentary filmmaking, Walker said, “Making a documentary is like living life.” It’s a different set of cards every time, and you have to look at your cards, study them and play the hand you’re dealt.

It’s something many audiences don’t often think about, but the attention to detail and meticulous nature of the job is all consuming. Walker likened the level of observation and attention she pays to her subjects to what you might find when madly falling in love—or stalking someone (that quote got a big laugh from the crowd.)

Walker also has this helpful tip for aspiring nonfiction filmmakers: “Always empower your subjects, even before shooting begins. They know their world better than you do. You’re a scuba diver in their ocean.” Dick concurred. He’s found that often the subject can tell you what the best shot would be, because they inhabit their world every minute of the day.

How do you choose a documentary subject or topic?

The first question from the audience asked the panelists how they chose their stories. For Timoner, the subject of her films has to be something that will be intriguing to her for at least a couple of years, since that’s the minimum amout of time it takes to complete any given project.

Walker finds it harder to make a film about a particular topic. Instead, she prefers narrative films. She looks for characters that are riveting, and follows that character through to the end. She also seeks out stories where she can visualize the beginning, middle, and end—the built-in structure often helps her in the editing process. Timoner concurs: “It’s like fractal theory,” she said. “The deeper you go into ONE story, the more universal it becomes.”

Dick always sticks with feature length documentaries versus short films. Since his work is often wrought with challenges, he feels that if the project were a short film then he would be giving himself an excuse to make an early exit. “I like to drive a film to the point of potential failure,” he said. “I like to have a target that I don’t know if I can reach.”

Timoner got a big laugh when she said that narcissism is a documentary filmmaker’s best friend, because you need a subject who actually wants to tell his or her story on camera, often baring some of their innermost secrets. Dick’s response echoed her sentiment: “It’s very important that your subject be an EXTROVERT.”

The surging influence of documentaries

From what Timoner has seen in recent years, the decision to make a documentary is no longer always a business decision. Citing Dick’s documentaries as examples, she thinks that nonfiction films as a genre has proven to have immense clout and impact—both politically and socially. “They go below and beneath where the news goes and they show points of view that never see the light of day otherwise,” she said.

Dick has personally witnessed the shift in the mindset and action of politicians after they’ve been confronted with his projects. “Politicians [absolutely] get influenced by documentary films. You think of politicians as completely calculating, but they’re also very emotional. When you show them a documentary film, they never get that kind of intensity coming at them.”

Continuous Improvement: Reflect-Refine-Evolve

One of the reasons why Walker prefers the documentary medium as opposed to scripted features is this: the documentary process allows literal, continuous improvement because it requires you to shoot footage, edit it and reflect on it to see what works and what doesn’t, show it to people for feedback, shoot some more footage, and repeat the process until you feel you’ve achieved what you set out to capture. The process for scripted features, on the other hand, is more linear. By the time you have a product that’s good enough to show to audiences, it’s almost too late to make any material adjustments.

The annual Coffee Talks, sponsored by Ovation took place June 5 at The Culver Hotel. The Directors panel is sponsored by Directors Guild of America, the Actors panel is sponsored by SAGindie, and the Screenwriters panel is sponsored by Writers Guild of America, West. Read previous recaps of the 2016 LA Film Festival Coffee Talks panels here and here.

This year’s 2016 LA Film Festival is currently happening at the ArcLight Cinemas in Culver City as additional venues citywide through June 9. Buy your tickets to all of our great screenings and special events today. Click here for more information.

To see our full lineup and Festival Guide, please visit our website, stay tuned to this blog and subscribe to our YouTube channel. Learn how to become a Member of Film Independent by clicking here.