The Otherworldly, Hellish Beauty of ‘Mad God’: a Conversation with Director and VFX maestro Phil Tippett

Behind the gruesome and the ugly, the macabre and the hellish, lives the beauty of potentially the most impressive independent stop motion film in history. Oscar-winning Visual Effects guru for Jurassic Park, Phil Tippett’s latest film, Mad God, is driven by its creator’s unconscious, a “mad god” himself, resulting in a tale of humanity’s attempt to simultaneously destroy and save itself. Writer-director Phil Tippett is a pioneer in stop motion, known for his brilliant creatures and curiosities found in major blockbusters the likes of Star Wars: Episode VI – Return of the Jedi, the Twilight film franchise, and RoboCop. His day job is as the founder and namesake of Tippett Studio, a premier full-service animation and visual effects production company headquartered in Berkeley, CA. While he is a master of this craft, he felt outpaced by digital animation in the prime of his career, which he witnessed firsthand in the production of Jurassic Park.

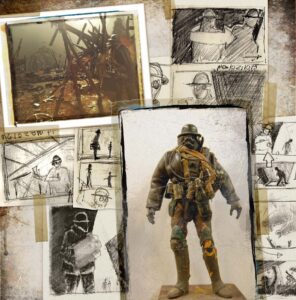

A modern-day Ray Harryhausen (VFX creator on Mighty Joe Young and Clash of the Titans), Tippett embarked on Mad God’s first scenes more than 30 years ago in his free time, revisiting the project 20 years later to finish the job with the help of friends and volunteers. In 2012, he created a Kickstarter campaign to complete the film, which features an outstanding variety of hellish landscapes and environments. The film feels like the fever dreams of all the greatest horror writers in history, punctuated by the fear of John Milton’s Paradise Lost, with echoes of the Second World War. It is beautiful, it is terrifying, it is otherworldly.

The dialogue-less film follows the dark character Assassin, who treks through a world torn apart by violence and fear in order to fulfill his purpose of either destroying or saving this forgotten place. The Assassin’s journey is filled with all of the darkest creatures in Tippett’s mind – the living expressions of pure ill, torment, futility, or sadness – for what is expected to be eternity. But is the Assassin here to save them? Or to liberate them from their misery, or to inflict worse?

The journey wasn’t just a wild ride for the characters; it was that way for the filmmakers, too. Everyone in the biz knows stop motion creators are some of the hardest working artists out there. Tippett claims he went on a Joseph Campbell-like experience to make this film – his dedication to the terrifying story even landed him in a psych ward before he could finish the film. Now, after a rebirth of his own, Tippett – like his characters in Mad God – can go on.

Mad God is certainly not for the faint of heart. Or for anyone in the midst of eating …. But it is for anyone hoping to witness an important moment in the history of stop motion filmmaking. Tippett is a master of the genre and this is his greatest work yet. Like the best of independent cinema, is it unbridled, uncensored, and unbelievable. Most viewers of Mad God may not have all the answers after watching the film, but Tippet does present them with enough hints to follow what he had in mind.

For a film with such scope and scale of abstraction – not to mention decades of work behind it –it was intriguing to go over the process of writing and tracking a story that began so long ago. We recently had a chance to sit down with Phil Tippett for a scintillating chat about the making of Mad God.

What was the first scene you filmed for Mad God?

Tippett: I think it was the big crane shot down into the hospital with the victim, the Assassin was about to be gutted.

Is that the scene that inspired you and filmmakers to complete the film years later?

Tippett: That was one of them. I shot about three minutes of material 30 years ago and put the thing on ice because the scale was too big and the crew dispersed to get other jobs. An early writing teacher of mine once told me: “The writer who writes in abstract has all the more responsibility to be clear.”

Over the 30-year process, how did the writing change for you, if at all?

Tippett: Well, the first thing I did was to write maybe 12 pages of what I wanted, focusing on tone, the rest were storyboards. But during that 20-year period that I spent before we rebooted the project, I had no reason to believe this thing would ever be made. But kind of like everything in my life, it was like a really slow burn. And I needed that. It’s not intentional; things [tend to] work in 20-year blocks, at least for me. Those 20 years was where I just let my unconscious go and do all the homework that I needed.

My wife was in the editorial department on Amadeus, so we would have dinner with [director] Miloš Forman. He gave me the best advice I ever got, which was, if you want to take a good shit, you have to eat well. That was a validation that the more time you have to think, the better. I don’t operate on intention, I let my unconscious percolate and let it tell me what to do.

How did you achieve such seamless continuity over the 30 years, with the ever-evolving changes in the stop motion process?

Tippett: We just did it! It’s that simple, and that’s what you do as a filmmaker. As they say, the canary sings one song. I don’t think about it that much. I know what the shot is and I’ve gotten to a point where I can just riff on things. If I’m doing a shot and I get a better idea, say 20 or 50 frames into it, I’ll just change what my intention is for the shot, if I think it’s gonna be better.

You made this film in your spare time after your day job. Do you feel that it was therapeutic for you?

Tippett: I think it was anti-therapeutic, actually. [laughs] I’m manic, not depressed. I mean I get depressed if my dog dies, but my superpower is my manic side – that just drives me and I don’t stop. Doing stuff all the time, I‘m exhausted by the end of the day, but my mind is still churning. So, I turned to alcohol just to stop it; that was my medication. And as the film went on, I really just started to disintegrate until I snapped and had to go into the psych ward and then spent six weeks in recovery.

It was a very Joseph Campbell-kind of journey for me, where the hero starts out meeting familiars and creatures that help him go on, guided by instinct and help from these other creatures. But eventually, the hero is on his own and ultimately dies and gets reborn. That’s really what happened to me, the whole thing right at the end. So, it was very much like a religious journey to me. Carl Jung wrote this book, The Red Book, and nobody knew about it. He wrote it over 16 years, but the same thing happened to him. Fortunately, his family helped pull him out of it and, I imagine, sent him to a psychiatrist.

Is there a reason that you decided to comment on the concept of gods in this film?

It was just kind of overarching, like our gods. Where are they? What are they doing? And I underscore that theme with the Leviticus quote in the beginning of the film: it’s a cruel God.

What gave you the most joy while making Mad God?

Tippett: Well, at the end there was no joy. [laughs] It was a compulsion. I would give the same answer that I imagine Mozart, Bach, or Beethoven would give when asked how they create their work. They would just point to the sky and say, “I didn’t do it. I just transcribed it. It was from God.” It was literally like that for me. My unconscious guides me, and a lot of times, I don’t know what I’m doing until it strikes me. I’ll have storyboards to explain things to other people because it’s all in my mind. When we rebooted it 12 years later, we cobbled together whatever we had. The first three minutes, the storyboards, and this 10-minute thing we put together 12 years ago. It’s pretty remarkable. The whole film is there in essence: 30 storyboards in three minutes, and it blocks out the whole thing.

When I began, my friend Alex Cox introduced me to the composer Dan Wool (Sid and Nancy) and the sound designer Richard Beggs (Children of Men). I was familiar with Dan’s music through Alex, and his scores for Alex were mostly Ennio Morricone-esque. I showed him the first three minutes, and then he went, “Mm, okay. I had a score previously [from] 30 years ago that Klaus Flouride from the Dead Kennedys did,” but it was a little bit too much on the nose. Then, I made a bunch of Hi8 sketches of different things around the house, like time lapses of worms in my compost pile, voices of my kids arguing in the background, a radio in the background where I’m just dialing through the channels. And that hit a chord with Dan because he was very much into ambient sound. So, we just connected on that level.

I didn’t want to fall into the trap of the temp track problem because I did not want to cut the film to something that wasn’t gonna be in it. You always fall in love with the temp track, and then you’re never pleased with what the composer does [for the film score]. So, Dan composed some stuff for that 10-minute section, and then the editor Ken Rogerson and I would hack that up as the film went along. I did a Kickstarter, and once I got the first 10 minutes or so, Dan and Richard would jump in and take it from there. I honed in early on the tone of the music because I wanted it to work hand-in-hand with the movie.

When did you know that Mad God was done?

Tippett: When it had to be! When the producers pulled the plug, we had to ship it. And Richard’s still working on it, hoping that at some point we can do a reboot.

What has the reception for Mad God been like from your perspective?

Tippett: It’s been exceptional; I’ve been overwhelmed with how it’s been greeted. It’s been showing domestically in theaters and picked up by a number of territories throughout the world. So, it seems to have found its audience. I was really surprised.

What can fans look forward to with your upcoming project(s)?

Tippett: I’m going to be talking to Shudder at the beginning of next year, and I have many projects that I’d like to do. After Mad God, I spent Covid designing a bunch of characters and shooting them against a blue screen and comping them into backgrounds. I’ve got 50 pieces of key art, 800 storyboards, and a script, and I am ready to go. It’s called Pequins Pendiquen. The title came up when I was in college with a buddy when we were smoking weed. I really don’t remember what the source of it was, but things like that stick with me. Anything that sticks, I kind of file away in my memory bank to use in a movie someday. Pequin is a shapeshifter and his objective is the Pendiquen. Again, it’s a typical Joseph Campbell story.

There are once-in-a-lifetime events – weddings, births, deaths, trips, squabbles, even – but they are powerful and fleeting. And then there once-in-a-lifetime films, and Mad God is one of them. Not only from the experience of viewing such profoundly unusual beauty and horror, but also from witnessing this historic feat of talent, patience, and creativity: much like the brush strokes of Monet and the music of Beethoven.

Mad God is available on the streaming platform Shudder.

Join. Watch. Vote. Become a Film Independent Member today to get exclusive access to watch the 2023 Spirit Awards nominees and vote to determine the winners!

Keep up with Film Independent…

[Header: ‘Mad God’]