Indie-pendent Study: Poetry and Politics in ‘Neruda’

Each month in Indie-pendent Study, Su Fang Tham explores films that have inspired her to dive into specific areas of interest, prompting her to research and learn about the subjects being depicted in detail well beyond the scope of the original film. Who says watching movies can’t also be educational!

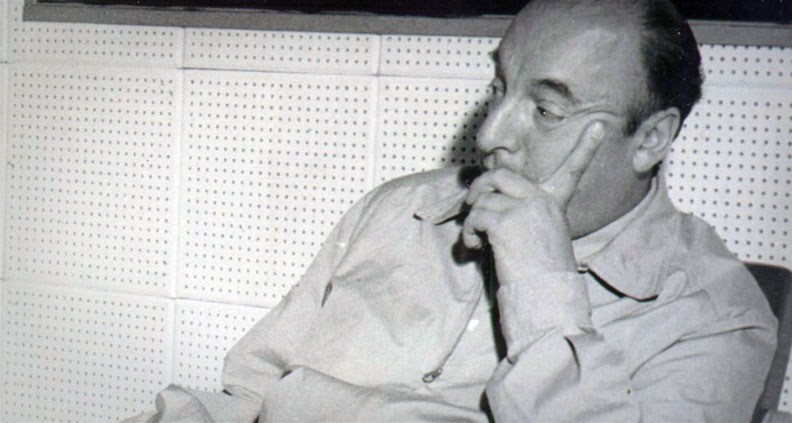

This month’s film: Neruda (2016, dir. Pablo Larraín)

Fresh off a nomination for Best Foreign Language Film at this year’s Golden Globe awards (airing this Sunday), Neruda is Chilean director Pablo Larraín’s latest meditation on his nation’s strife under multiple decades of totalitarian rule. This time Larraín’s focus is post-WWII Chile, where in 1948 famed poet and leftist senator Pablo Neruda was forced to escape underground, and later into exile, when the government declared war on communism.

Neruda marks Larraín’s second major release in a very big year for the auteur, whose Jacqueline Kennedy biopic Jackie is also currently in release, nominated for four Film Independent Spirit Awards including Best Feature, Best Female Lead, Best Editing and Best Director for Larraín himself.

The film’s opening scene lets viewers know that the film will not be a straight-laced biopic about the Nobel Laureate, but rather an eccentric and surreal take on the life of its titular subject: in the middle of a heated discussion in what looks like the lounge of a senate chamber, Neruda (Chilean actor Luis Gnecco) casually uses one of the urinals on one side of the room as he continues to field acerbic jabs from political opponents. If that’s not one of the best allegories about the nasty and depraved nature of politics ever put on film, I don’t know what is.

The hook in Larraín’s take on Neruda’s life is not so much in how the poet is portrayed, but in the character of police inspector Oscar Peluchonneau—a baffling, awkward and fictional addition to the Neruda story. Gael García Bernal plays the cartoonish inspector, who is tasked to turn the country inside out in order to apprehend the poet and presumably crush the hopes and dreams of the millions of people he has inspired. Or so it seems…

Narrated from both men’s perspectives at different intervals, we soon suspect that Neruda may be purposely leaving clues for his pursuer, almost as if he wants to get caught. [Spoiler alert] Once we realize that Peluchonneau is nothing more than a fabrication in Neruda’s mind, that’s when Larraín and screenwriter Guillermo Calderón’s brilliant execution comes to an apex. It also explains why Neruda treats his (imaginary) nemesis with such kindness and empathy towards the end of the film. As Peluchonneau lay freezing to death in the thick snowy Andes mountains, Neruda came to his aid and risks his own life by carrying the dead corpse back down the mountain to be buried. [End spoilers]

As Neruda narrowly escapes Peluchonneau’s grasp time and again, the audience is treated to the “champagne communist’s” extravagant lifestyle alongside his aristocratic Argentine wife Delia del Carril (Mercedes Morán). The character of Nerduda’s sense of self-importance comes through vividly when he snaps at her one day at the height of a lover’s spat: “Kill yourself if you want to. That way, I’ll write about you for another 20 years.” By contrast, del Carril’s love for her spouse is best captured by her parting words to him: “Life with you is beautiful, it’s like living on a tree-lined street.”

Further Study: Pablo Neruda, 101

Perhaps the most lauded Latin American poet of the 20th century, Pablo Neruda was born Ricardo Eliécer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto and began writing poetry at 10, taking the now-famous name as a nom de plume because his father objected to his aspirations as a poet. He ultimately adopted the name “Pablo Neruda” legally in 1946.

In his early days, Neruda held the position of consul in countries such as Burma (modern Myanmar), Sri Lanka, Singapore and Java (modern Indonesia), where he met his first wife, a Dutch bank employee named Marie Antoinette Haagenar Vogelzang. Delia del Carril was his second wife, until their divorce in early 1950’s.

The Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) and the death of his close friend, Spanish poet Federico García Lorca, is said to have heavily influenced Neruda’s political ideology, pushing him toward communism.

In 1971, Neruda was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature “for a poetry that with the action of an elemental force brings alive a continent’s destiny and dreams.” To to this day, his legacy remains pervasive in Chilean life, including education and culture.

For a look at four of his poems with accompanying English translations, click here.

Neruda was also a passionate collector of various items throughout his life, and in fact three of his houses in Chile are now on display to the public as museums: La Chascona in Santiago, where he lived with his third wife, Matilde Urrutia, until his death in 1973; La Sebastiana, in Valparaíso; and his house in Isla Negra (aka “Black Island”) along Chile’s coastal region.

For a highly enlightening account of a visit to all three houses, please check out this article from The New York Times.

The 2017 Film Independent Spirit Awards happen on February 25 and will be broadcast live on IFC at 2:oopm PT / 5:oopm ET. This year’s hosts are none other than the great John Mulaney and Nick Kroll—don’t forget to tune in!

For more information about the Spirit Awards, including a full list of nominees, just click here. Follow us on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube for more updates. Not a Member of Film Independent yet? Become one today.