Guest Post: How I Shot My Horror Feature Debut Entirely on iPhone

I’ve always been attracted to American cinema and culture. My favorite films are all American, and I always wanted to live in California.

When my film The Black Cat was selected to the HollyShorts Film Festival, I decided to fly to Los Angeles. I had a terrific experience—the helicopters, sirens and big cars were all part of the appeal. In LA, it felt like I was in the movies.

At HollyShorts I met Eli Roth, there to premiere his Cabin Fever director’s cut. Roth gave me a challenge: to make a feature—a slasher movie—where I’d do everything myself. Following a five-month screenwriting course back home in France, I returned to LA with my enthusiasm, a feature script written in French and Eli Roth’s challenge. The original script I’d written was quite expensive. So I wrote another. This one was in English, but still too expensive to produce myself. So I wrote a third: a $10,000 movie script called SCRATCH.

SCRATCH’s idea was to build from scratch. I had no connections in LA. So how could I make a first feature? As my drama teacher used to say, “Constraint is freeing.” So I built on my constraints. The movie would be about where I was precisely at that moment: Ground Zero of the indie-filmmaking hustle.

SCRATCH would be the story of a wannabe filmmaker shooting a music video for a local metal band on a shoestring budget. By accident, I had discovered the ruins of the old Los Angeles Zoo while hiking in Griffith Park. As soon as I saw the location, I decided to make a film about it. Rusty, empty cages… I’ve always seen zoos animals as prisons, and I would talk about the beast inside us—the freeing of the self.

So here’s how I handled shooting 51 minutes film with just an iPhone. Long story short, I turned every problem I had into an asset:

- I couldn’t rent a camera; therefore, I shot on the iPhone

- I just had a laptop; therefore, the HD format would be light enough

- I didn’t have time off; therefore, this would be the story of a hustled shoot

- I didn’t have time to sculpt light; therefore, we would shoot outside during the day

I would tell the story of a clumsy filmmaker, and the film would be composed of his footage. The conditions depicted on the screen would be as close as possible to the actual conditions of the shooting.

At the time, I was working at a school as a teacher, writing the script between recess and bell rings. Summer was coming and that would give me two months to shoot and wrap. I knew that in order to make the film work, I needed two things:

- Decent catering, and

- Decent sound

I focused on first finding a sound guy that would be kind enough to work for very little money. I was aiming for one location, so we used every corner of the Old Zoo. That meant we would have to run uphill, downhill, between the trees, all week long. No time for a truck or cart. Sound had to move as fast as I could with my iPhone. I posted an ad on Craigslist. I had some replies saying I was “out of my friggin’ skull.” I met a few sound people. Finally, Joe Bartone fell in love with our “French touch”—he wasn’t scared of our guerrilla adventure.

I had two French friends come to help me out—from San Francisco and Marseille, respectively. One would help me prepare the shoot: an AD, script supervisor, coach and producer. The other would come before the shooting as a Grip: a no-nonsense “Mr. Wolf” type.

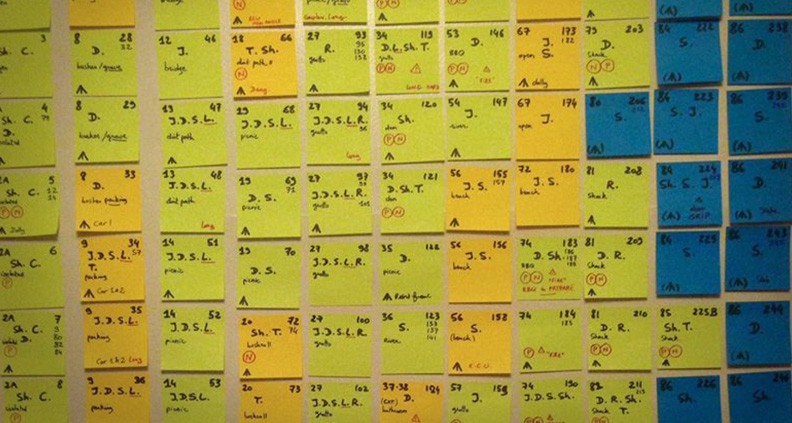

If you have a story that allows you to skip the lighting process, all that’s left is to set the angle, lens, filter and sound. We used sticky notes—one per shot. On the sticky note we’d write 1) if the shot needed a tripod 2) who was in it 3) the location and 4) if it would require a permit. We put all our post-its on a wall and sorted them to make more sense.

While prepping the shoot, we were also auditioning actors. This alone took one month. We used an audition facility that was free to use but required that we audition some of the facility’s members as part of the process. At first I figured, “Okay, I have to spend half of my time casting people I don’t want to see but hey, it’s free.” Turns out, the “mandatory” talent we discovered at that place were amazing and constituted half of the final cast. Note to actors around here: do not hesitate in joining a casting audition facility.

Shooting with an iPhone entailed a whole bunch of technical specificities. As a tool, it’s small—light as a feather. It’s the lens, camera, display and processor, all in one. Plus there are a ton of filming apps available.

In the film, “Jack” (Chris Bound), the director, and his assistant “Dave” (Joe Martone) have their iPhones strapped to their forehead. In order for me, as director-DP-cameraman, to impersonate Jack or Dave’s point-of-view, I had to have the iPhone at my forehead while being able to look at it, since the display is right behind the lens. To this end, we used a flexible portable tripod, folding it so that two of its feet were sitting on my cheekbones. The third I would hold with my hand. I used my head to move the camera and my hand to adjust the tilt. My eyes were only a few inches from the display—the iPhone screen—and I had to move using my peripheral vision, all while securing the frame.

The actor I was impersonating would be right behind me to say the lines and have his hands enter the frame when needed; the sound mixer would be right behind us, holding the microphone so that it didn’t enter the frame as the three of us moved around.

In order to have some more creative play, I had ordered a wide-angle lens and a tele- lens for iPhone. No lens for iPhone is great, but at least I had three angles to tell my story. I had built a belt holster that would contain the two lenses, that I could take out and swap quickly between takes.

The sensor of the iPhone—while being an absolute wonder—is limited in its light range. So I ordered plastic ND filters of various densities and designed a 3D-printed filter-holder to help adjust the light. During tests, I decided to always choose exposure on the brightest point, because you can always get more info from a dark spot than when the picture is clipped. If at any time during the actual shoot I messed up with all this I could always attribute it to “Jack” being scandalously unprofessional.

Some shots required a dolly, which I built out of PVC pipes assembled together with a few screws and skateboard wheels. The dolly tracks were stabilized with socks filled with sand. The portable LED lights I’d bought to cut the shadows were in fact used as work lights while setting camp at 4am. The deflectors ended up being used solely to protect actors from the sun between takes. Gear was also used as props. And even though we had a permit, the tent and production village still had to be completely taken apart and rebuild every morning! Everything had to be done quick, quick, quick. We’re talking about 30 setups a day.

We actually shot some sequences in the Old Zoo’s animal dwellings, which had been the den of graffiti taggers for years. So the day prior to shooting, my two French compatriots and I went there with rubber gloves bags and cleaning detergent, picking up eons of dead leaves, broken glass, beer cans, paint cans and used condoms. We removed dozens of pounds of grime and brushed and cleaned up the concrete to be ready for our actors’ bare feet when they play the savages.

There were also a few wicked metal stumps, here and there, over which we shoved tennis balls to make the place foolproof.

Before the first day of the shoot even began we were already completely exhausted. Passion gave us wings, though. We were so exited. Any director who reads this knows what I am talking about: this is almost the reason why we make movies. And by the first day of the shooting, we were ready.

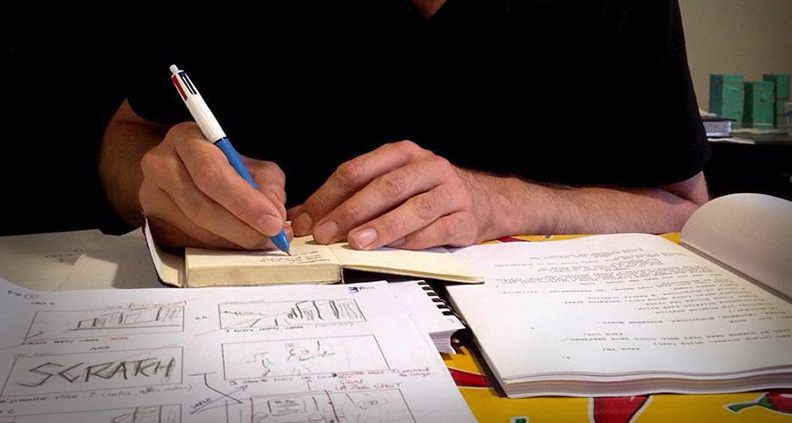

We had introduced the location to the cast and crew. We had rehearsed the most complex scenes. FilmLA and the Park Rangers knew where we were shooting. We had a nice shooting schedule. I had a little book with each shot numbered, where to put the camera, which lens, what to say to the actors. I love my little book method; it helps me keep my cool, shows me the way at all times.

We were determined as can be, and determination is all you need.

We had bought a lot of material—including the iPhones—that we returned after the shoot. Some stores give you several weeks to return what you bought. We raised some $10K on Indiegogo for post-production. We took another week to shoot secondary shots. Most of the SFX were practical effects straight out of the Eighties. The opening “SCRATCH” lettering that appears on the screen was shot by covering a glass with black slime and scratching the surface to let light shine through, with the iPhone filming from underneath. Talk about epic DIY!

The film was edited on a laptop, on weekends. I edited the film myself. I also graded it myself—but I would advise against it. Have an editor help you out, or else it’s a bit like Bruce Willis pulling out his own teeth in 12 Monkeys.

The film was shot in August 2015 and finished in April 2018. Now it is going for the Festivals run, and the first festival to examine it selected it and awarded it: the Mediterranean Film Festival in Syracuse, Sicilia. We are thrilled. SCRATCH was designed as a door-opener—something to put me on the map.

Up next is my adaptation of Stephen King’s novella Grey Matter and an ambitious feature project called the Chondrocylordrome. And this time, I won’t be using an iPhone!

To see what else Tristan Convert is up to, please visit his website or follow him on Twitter. To learn more about iPhone shooting, please check out our blog.

Learn how to become a Member of Film Independent by visiting our website, and click here to subscribe to our YouTube channel. Be sure to follow Film Independent on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.