ICYMI: Four Modern Indie Directors Indebted to Italian Neorealism

Editor’s Note: the following post originally ran in June of this year, it is being re-posted here with minor edits. Special thanks to author Jesse Gutierrez.

***

Italian Neorealism has always been ingrained in the fabric of independent arthouse cinema. With its scrappy, documentary-like attitude dating back to the tail end of WWII, I have long considered filmmakers like Roberto Rossellini and Vittorio De Sica to be some of the pioneers of modern day low-budget filmmaking.

Instrumental in popularizing long and quiet takes, run-and-gun on-location shooting styles, the regular use of non-professional actors and stories often centered around rarely depicted communities in difficult economic conditions, their impact on today’s independent film landscape is undeniable.

It’s clear to see how deeply embedded Italian Neorealism is in the DNA of today’s indie film scene. To better understand the principals of Italian Neorealism, check out this Sight & Sound video essay from the filmmaker Kogonada:

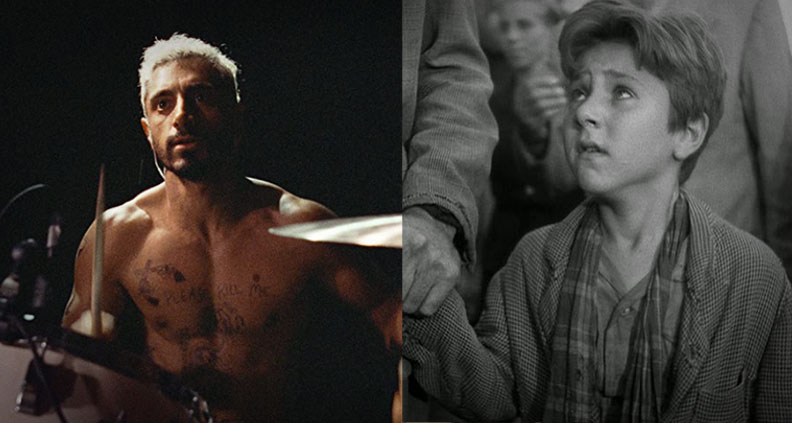

Filmmakers like Kelly Reichardt, Eliza Hittman and this year’s winner for Best Director have long employed these Italian Neorealist techniques and aesthetics to their films to great effect. And Spirit Award winner Darius Marder’s first foray into narrative storytelling from documentary naturally utilizes some of these conventions to bring life and authenticity to Sound of Metal. Here is how Italian Neorealism is being kept alive by this talented crop of young filmmakers…

KELLY REICHARDT

How, What, Why: Ever since my introduction to Kelly Reichardt’s work via 2008’s Wendy and Lucy (a 2009 Spirit Awards nominee for Best Feature), the parallels between her filmmaking aesthetic and that of the Italian Neorealism were clear. Vittorio De Sica’s Umberto D (1952) in particular came to mind as a possible influence of the film—superficially, both feature a protagonist and their dog at the center of their story, but the parallels run deeper, as both films share the theme of transient souls lost in the difficult economic landscapes of their time. As Kelly once said during a talk with the BFI, “My films are about people who don’t have a safety net.” What line can better define the both the neorealist movement that began in the mid 1940s and her own work? 2020’s First Cow also fits this neorealist mold with its authentically told story of two gentle souls desperately searching for a means to stay afloat in the burgeoning Pacific Northwest, a tale carefully executed and told with profound clarity and pace that rivals that of De Sica.

ELIZA HITTMAN

How, What, Why: Eliza Hittman’s third feature, Never Rarely Sometimes Always (nominated for a leading seven nominations at this years Spirit Awards!) along with her previous films, It Felt Like Love and Beach Rats, could have easily been plucked out of the Italian Neorealist movement of days past. In her exploration of New York suburban youth making sense of their sexuality and the world around them, Eliza employs a signature Neorealist technique of casting non-professional actors in central or important roles—much like De Sica, who famously casted Lamberto Maggiorani and Enzo Staiola as the leads in Bicycle Thieves (1948) for their typical and expressive qualities and their ability to elicit the emotion and the sympathy of the viewer. In his view, “the man in the street, particularly if he is directed by someone who is himself an actor, is raw material that can be molded at will.” Hittman uttered a similar sentiment in her interview with Variety when she talked about the casting of non-actor, Sidney Flanigan, as the star of her acclaimed new film: “I think I’m interested in all different kinds of performers whenever I think about casting a film, and they don’t necessarily have to be actors… you could feel that Sidney had a story inside her.”

CHLOÉ ZHAO

How, What, Why: Throughout her young career, Chloé Zhao has journeyed through Appalachia and, just as the neorealists in war-torn Italy, has turned her lens to rarely depicted communities faced with economic hardship. In Songs My Brothers Taught Me, she explores life in an Indian reservation where the effects of alcoholism have taken a hold of the community. Reminiscent of Roberto Rossellini’s War Trilogy, Zhao utilizes ordinary, everyday humble locations, a stripped down aesthetic, and casts a majority non-professional actors seemingly playing themselves. In The Rider, she centers her story around real-life elements from lead actor, Brady Jandreau’s life, who suffered a brain injury during a rodeo accident and in this year’s Spirit Award Best Feature winner Nomadland, she wove in authentic nomads with her fictional central character to achieve a documentary-like feel to her story. These realist elements are central to her work and central to some of the strongest voices working in independent cinema today.

DARIUS MARDER

How, What, Why: As a narrative filmmaker, Darius Marder, utilizes his background as a documentarian to employ this realistic aesthetic that was so central to Italian Neorealism. With Sound of Metal, Spirit Award winner for Best First Feature, he shows us a glimpse of both the deaf and recovery communities that have been underrepresented in cinema. He casts deaf actors in surrounding roles, bringing an authenticity to the story that made Italian Neorealism so intriguing. Much like Bicycle Thieves (1948) we witness a complete loss of livelihood—on one hand, the loss of hearing that destroys the career of a touring musician, and on the other, the theft of a bicycle that ruins a chance of prosperity in the depressed post-WWII Italian economy. Marder is an exciting example of an up and coming filmmaker keeping the Italian Neorealist spirit alive today.

Film Independent promotes unique independent voices, providing a wide variety of resources to help filmmakers create and advance new work. To support our efforts with a donation, please click here and become a Member of Film Independent here.

Follow Film Independent…

(Header: Bicycle Thieves)