Directors Close-Up: Five Best Documentary Nominees with Not Much in Common

“The definition of documentary film goes back to someone having a hard time describing it.” So said Procession filmmaker Robert Greene, in the third session of Film Independent’s 2022 Directors Close-Up on February 9. The third panel of the weekly DCU series, which continues Wednesdays through March 16 including three in person sessions at the Landmark Theatres in Los Angeles—passes and individual night tickets here—was an action-packed doubleheader, with two in-depth filmmaker panels unpacking the art and economics of nonfiction cinema; the first, featuring the five directors nominated for Best Documentary Feature.

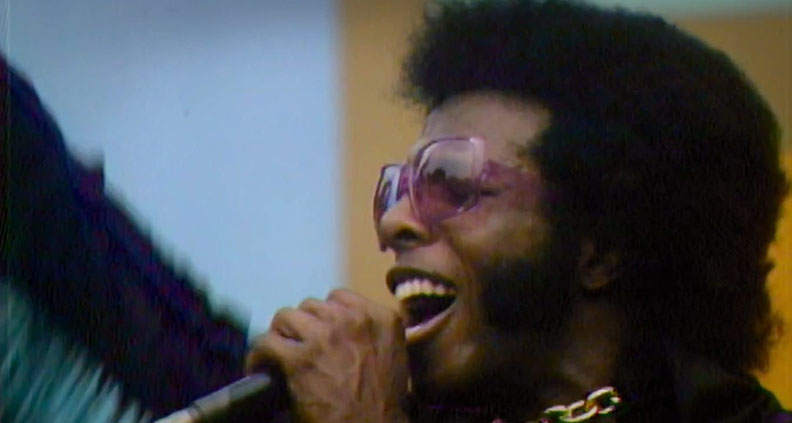

Greene—joined by fellow nominees Jessica Kingdon (Ascension), Jonas Poher Rasmussen (Flee), Nanfu Wang (In the Same Breath) and Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson (Summer of Soul …Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised)—cited nonfiction film pioneer, and coiner of the term “documentary”, John Grierson’s description of the medium as “a creative treatment of actuality.” A recurring theme of the panel, moderated by Shirkers director Sandi Tan, was the multitude of ways in which this year’s Best Documentary nominees have approached their medium of choice.

The result was a convivial discussion of process, stylistic approach and a vigorous appeal for critics and consumers to recognize Documentary’s breadth and relevancy. Here are some of the highlights:

A DIFFERENT TYPE OF NARRATIVE, PART ONE

The hardest part is getting started. Tan began by asking the filmmakers what they felt was the most difficult thing they had to overcome in order to make their docs. Questlove said he felt like “a musical Atlas carrying this world on my shoulders,” combing through hundred of hours of long-lost footage of the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival to create the indispensable historical document Summer of Soul. “I had to get over myself, the trepidation and self-doubt I had that I was able to take on a task I felt was so important.” For Wang, whose In the Same Breath chronicles and compares the (largely failed) COVID-19 response of both China and the US, “The reality was chaotic, I lived in confusion,” saying she had to find a way to “diagnose, process and present” that reality to the audience.

Drawn to storytelling. Rasmussen’s Flee recounts the horrific refugee experiences of his friend (not his real name) Amin’s exodus from Afghanistan. The story is told via animation, not just to preserve “Amin’s” identity but also as an artistic choice. “To me the biggest fear was finding a style of animation that I felt could represent his testimony and support his story.” There was also the difficulty of convincing potential investors that animation was viable style for telling a real-life story (despite there being an increasing number of such films in recent years).

When a plan comes together. Tan asked the panel what the precise moment was they finally felt they had something special. For Kingdon, whose Ascension is an impressionistic portrait of modern China as seen through a series of artful vignettes, that moment came during editing. “I was in a rough cut lab… I showed one sequence where nobody asked that question,” she said, referring to an inquiry she had began to dread, about obtaining filming access in her locations, which she felt had become annoyingly persistent. “I realized they were responding to the material. Not the process.” For Wang, it was watching the dailies of a 20-minute unbroken shot of paramedics rolling an empty gurney through the deserted streets of her hometown, Nanchang—streets she had never seen empty before.

It’s about time. Tan asked, “How do you deal with time in your film?” For Rasmussen, it was key to create a sense of immediacy while collecting his subject’s testimony. During their interviews, he asked Amin to close his eyes and recount his memories in the present tense, always by first describing the physical details of the location. Doing so, “He would relive these memories rather than re-telling them,” he said. Said Questlove: “Time is the actual story of my film.” Far from being a mere concert film, it was important that Summer of Soul capture the Black national mood, he said, in the transitional years between the early Civil Rights movement and the Black Panther radicalism of the 1970s.

Filmmaking on the edge. “It was tricky,” said Greene about the making of Procession, an intense look a group of Catholic priest sex-abuse survivors undergoing a radical experiment in drama therapy. Working with such sensitive material (and fragile subjects) was difficult. “We thought every shoot could be the last one,” saying that the very first day of shooting “was a total disaster,” throwing the whole project into doubt. It was one of his subjects, Ed, who insisted on returning the site of his abuse—a creative turning point that got things back on track.

Variety is the spice of (real) life. In closing, Tan asked the panel if they agreed with her that “Documentary” was not a genre but rather a medium capable of holding many different genres. With the panel agreeing, Greene said to just look at the nominees’ own projects: “To me, the variation is the evidence that nonfiction film is the most vibrant form of cinema. Period.”

The 2022 Directors Close-Up is supported by Premier Sponsors Directors Guild of America, Landmark Theatres and SAGIndie. Supporting Sponsor is the Mississippi Film Office.

The Film Independent Spirit Awards are supported by Premier Sponsor IFC and FIJI Water, the Official Water. To join Film Independent and vote on the Spirit Awards, please visit filmindependent.org/join

The Spirit Awards are the primary fundraiser for Film Independent’s year-round programs, which cultivate the careers of emerging filmmakers and promote diversity and inclusion in the film industry. Support our work with a donation.