Detail Oriented: Meet the Puppet Master Who Brought Wes Anderson’s ‘Isle of Dogs’ to Life

Movies are a mosaic of moving parts. But we don’t always see which parts, or who’s moving them. Each month in Detail Oriented, Su Fang Tham explores some of the more specialized areas—and career paths—related to film production.

***

Nominated just yesterday for the Best Animated Feature Oscar at the Academy Awards and garnering two Golden Globe and BAFTA noms apiece, Fox Searchlight’s animated entry into the 2019 awards sweepstakes is Isle of Dogs—filmmaker Wes Anderson’s second stop-motion feature following 2009’s Roald Dahl adaptation Fantastic Mr. Fox.

Based on Anderson’s original screenplay with a story by Anderson, Roman Coppola, Jason Schwartzman and Kunichi Nomkura, Isle of Dogs (now available on streaming and BluRay/DVD) is set in the fantastical dystopian Japanese city of Megasaki City, where the government wrestles to control an outbreak of canine flu, decreeing that all dogs must be quarantined to a massive garbage dump dubbed “Trash Island.” Devastated to lose his beloved bodyguard dog Spots (voiced by Liev Schrieber), 12-year-old boy Atari (Koyu Rankin) runs off on a grand adventure to look for him.

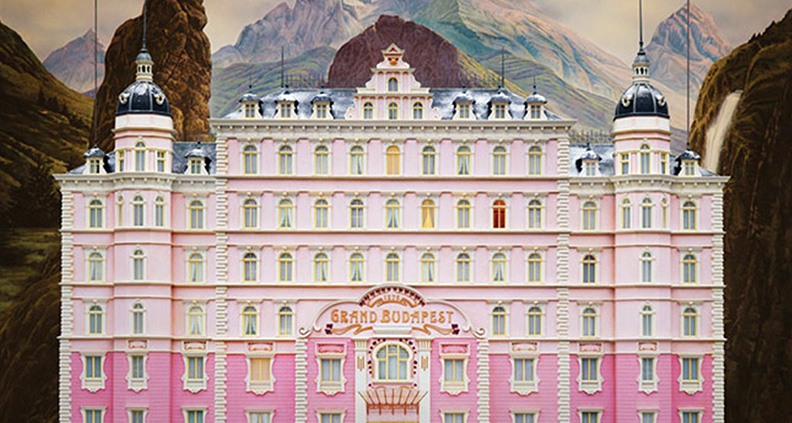

Puppet-maker Andy Gent previously collaborated with Anderson on Fantastic Mr. Fox and Grand Budapest Hotel. For this animated adventure, Gent’s team faced the daunting task of transforming between 60 and 70 sculpture templates into 1,105 animate-able puppets—dogs, humans and the 2,000+ background characters in the film. Here’s how he and his team designed and made puppets in five different sizes for various phases of the shoot and brought to life each animal’s personality:

ANDY GENT

How did you first get into puppet fabrication for filmmaking?

Gent: I studied illustration at university. I thought I’d try making pose-able figures to photograph in little sets that I’d built instead of drawing and painting them like my fellow students. I always liked making things. My dad was a cabinetmaker, so from an early age I was encouraged to make my own fun in his workshop.

Why did some of the puppets have to be made in five different scales: oversized, large, medium small and extra small?

Gent: The main scale, which we call “hero scale,” does most of the work—it’s the best size to fit all the intricate mechanisms into it that make a puppet tick. The “hero scale” puppet can talk and emote and move in every way necessary. The dogs at the beginning are smaller than their human masters. But once their size is set, their environments can be built to give them the backgrounds to the scenes and places in the story. That means the “hero scale” gets pretty big pretty quickly, especially if it’s a wide-open exterior.

And then we make a half “hero scale” puppet, which does many—but not all—of the things of its bigger-scale cousin. This has the advantage of creating bigger scenes to show more of the world. We then have to reduce the set by half again and again until you can build the streets, the cities and islands that are small enough to fit into the shooting stages and not take up too much space.

We had roughly 50 sets in operation at any one time. If they were all huge, we’d only be able to fit two into a stage and shooting would be really slow and very, very expensive. There’s also the aesthetic of small-scale—Wes likes the charm of the miniatures—they move and look a little differently due to materials and how they can be touched. So scale has an element of aesthetic to it as well. The “oversized scale” is rarely used, but allows us to make very intricate things to emphasize the meticulous detail. For example, Spots’ “oversized scale” missile tooth wouldn’t be possible in “hero scale.” We just made a part of his mouth big enough to read the writing [on the tooth].

How did you make each of the dog’s personalities, expressions and idiosyncrasies shine through?

Gent: Through study and observation of many dogs, especially my own Labrador— Charlie—and how he emotes with his eyes, ears and mouth. How he holds his head when he’s alert or tired and then trying to translate this into tiny mechanical pieces that control the outer form from within. This, along with the experiences of some 60+ amazing, super-skilled makers, months and months of time and money, some crazy materials and then handing them over to the amazing animators. The word “animate” really sums it up: to breathe life into the puppet. To me, after all this work, you look at a finished shot and go, “Wow! That dog just spoke to that boy!” You’ve forgotten that you actually made them! That’s the little bit of magic that gets mixed in too.

Why did you decide to use alpaca, mohair and merino wool for the fur?

Gent: Simply because it’s shorn and so no animal gets hurt for its hide. From a technical perspective, the natural material dyes more easily, unlike synthetic materials which are trickier to use.

What was the collaboration process between your team and Jason Stalman’s animation team? Were both teams involved from the start?

Gent: We always start so much earlier than Jason’s team, but when we get to armature work we start to test with the animators to find what the puppet can and can’t do. Then we really work together; it’s like designing a Formula One racecar where you need to build it with its driver in mind because he needs it to do his bidding. Puppets don’t always do what you want, so they’re often being adapted to get a new movement or pose that wasn’t expected 12 months earlier in the creation process.

What was the process like working on the some 60-70 sculptures of the individual dogs that ended up in the film?

Gent: Great! It was almost a free hand in their creation. Wes just said: “Sculpt me some dogs, Andy. They are disheveled, flea bitten, starving, matted mutts.” We really went to town sculpting them quickly in a form that I call Giacometti-like—rough but full of character. These are one or two day sculpts. They capture broad strong looks quickly and are basically three-dimensional sketches. When Wes liked a sculpt or look or pose, he’d ask us to keep that and go from there when we worked on a new one, putting bits from this or that together into the next sculpt. It was very fun and organic, these colorful three-dimensional characters really emerged out of the clay.

Isle of Dogs is currently on BluRay/DVD and SVOD. To learn more about the making of the film—including inside tidbits from its voice cast—check out our 2018 recap of a special Film Independent Presents preview screening of the film.

To learn more, check out past Detail Oriented columns on our blog. Not a Member of Film Independent yet? Become one today. Subscribe to our YouTube channel and follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.