ICYMI: Celluloid vs. Digital, Where Are We Now? Checking in with ‘Side by Side’

NOTE: the below piece originally ran in July of 2020. It’s being re-posted here with minor edits. Special thanks to author Su Fang Tham.

***

In the 25 or so years since digital photography first debuted, such technologies have steadily grown to take over all aspects of feature filmmaking – from image acquisition and editing to distribution and exhibition. In 2002, George Lucas’s Star Wars: Episode II: Attack of the Clones became the first major feature to be shot entirely on digital. Seven years later, Slumdog Millionaire – shot primarily on digital – won an Oscar for Best Cinematography.

By 2013, the number of major films shot digitally finally outnumbered those shot on celluloid. The next year, Paramount announced it would no longer release 35mm prints in the U.S. For the first time, the prospect of no longer having access to celluloid film stock became an imminent concern for DPs worldwide.

Fortunately for film manufacturers like Kodak, director Christopher Nolan – one of celluloid’s staunchest defenders – led a coalition of A-list directors in lobbying major Hollywood studios to commit to buying undisclosed amounts of film stock, thereby ensuring the supply at least for a while (the deal was recently renewed, so film enthusiasts can take a breather–for now.)

By the time 2018 rolled around, only 24 of the major studio films released were shot on 35mm. Even so, it looks like film might still have a fighting chance, with several of 2019’s biggest awards season players being shot on film–including Once Upon a Time… In Hollywood, Lady Bird, The Lighthouse and Marriage Story. And assuming the studios are done reshuffling the release calendar for the rest of this year (ha!), several of 2020’s most highly anticipated blockbusters are also shot on celluloid: Nolan’s Tenet, Patty Jenkins’ Wonder Woman 1984 and Daniel Craig’s latest James Bond outing, No Time To Die.

When the celluloid vs. digital debate reached a tipping point around 2010, director Chris Kenneally and producer/narrator Keanu Reeves chronicled the transition with Side by Side (2012) – a critically-acclaimed documentary that not only dug deep into the issue, but which also took viewers on an eye-opening tutorial on the history and lifecycle of filmmaking.

With several big-name celluloid releases looming, we sat down with Kenneally to see where we stand, nearly ten years on from Side by Side‘s release, in the fight to preserve a century-old medium while still embracing modern tools and technologies.

CHRIS KENNEALLY

Any discussion on this topic can quickly become technical and risk losing the general audience. But Side by Side did a brilliant job of straddling that balance – how did you do it?

Kenneally: Our goal, first and foremost, was to make it engaging and entertaining, but educational as well. So I’m glad to hear you say that. Every now and then, I’ll hear that some film schools are using it as part of the syllabus.

What drew you to this project?

Kenneally: I was the post-production supervisor on Henry’s Crime (2010); Keanu was the film’s lead and its producer, so he was often around when we worked on color correction. Since it was shot on film, we had to match the digital color correction to what was shot on film. We literally had to play the filmed and digitally corrected version side-by-side. That’s when Keanu came up with the idea – “We should do a movie about this!”

What the documentary ultimately became was very impressive – you had so much material from those interviews that, two years later, five Side by Side Extra DVDs were released, with full-length interviews from 16 of the directors/cinematographers featured in the documentary.

Kenneally: We started with people I knew at [post-production house] Sixteen19 [now a part of Company 3] and Technicolor, and then we went to Camerimage – a film festival for photographers and DPs in Poland. There was a blizzard and we were all stuck in this small town. So we talked to some of the best directors and cinematographers right off the bat. It really informed us a lot more about the deeply rooted issues. The filmmakers there helped us get access to even more experts – we went on to the UK, Denmark, Morocco, Germany and ended up interviewing 117 filmmakers over a-year-and-a-half!

In 2012, we were at a tipping point. Digital was threatening the extinction of emulsion. The tone of the documentary really lamented the end of film. Now, its 2020. To reiterate Reeves’ question in the opening of the doc, “Is this the end of film?”

Kenneally: Yes, I think so. The two reasons some might still prefer film are image acquisition and the grainy/organic visual quality of film. If you’re going to choose film now, it’s an intangible look-and-feel argument and no longer a mathematical argument. Digital didn’t use to have sufficient resolution and dynamic range, but now the dynamic range of dark to light and resolution has far surpassed film.

Many celluloid advocates would say skin tone colors still look more natural on film.

Kenneally: It depends on how the color correction is done – even when you shoot on film, you digitize and then manipulate it digitally to arrive at what you want. But with a photochemical bath, you don’t have as much room to manipulate the images as you can with digital.

Even for projects shot on film, you still need to convert it to digital for color correction?

Kenneally: You don’t have to, but the entire system is now a digital pipeline. For VFX to be done, they need digital material; same for color correction. Almost all movie theaters project digitally now – to watch a film on 70mm now is a special event. Filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino and Christopher Nolan have the resources to shoot on film and have it processed in a lab. But everything still has to be processed digitally to a certain point to get it into the pipeline for VFX, color correction and exhibition. Archiving to film doesn’t happen very much either.

The stability and consistency of digital archival was a problem in 2012, with the rapid upgrades of formats and readers/machines becoming obsolete. Martin Scorsese said that celluloid is still the only archival format that will still be around 60 years from now. Where are we now on that front?

Kenneally: [Steven] Soderbergh said the opposite in the doc, that what you create digitally has a better chance of longevity. Digital content is stored on LTO magnetic tapes that lasts 50–100 years, there’s LTO 5, 6, 7, I think we’re up to 8 now. You should make multiple backup copies, which is what I did with my most recent film, Already Gone. Back up your dailies and the final copy of your film on LTO tapes and then have other copies stored in different places and vaults – it’s called geo-separating. Movies now also exist on multiple streaming services, so digitally it’s stored in the cloud, not to mention the distributors also have the DCP [Digital Cinema Package]. I still remember carrying around the film reels when I started in the business.

Ten years from now, are you confident that someone could still watch Already Gone on some type of format?

Kenneally: I am…. because iTunes, Amazon, etc. has it in their library and handle format upgrades. For content that isn’t on a streaming platform, it might still be an issue. In general, as long as you make copies and store it properly, you should be fine. If you have the opportunity to store it on film, definitely do that; but it can get expensive.

Between 2015 and 2017, only 4% of sci-fi movies were shot purely on film, but for dramas, that number was 17%. What do you make of this?

Kenneally: There were two frontiers that ushered in the use of digital. One was sci-fi blockbusters from filmmakers like George Lucas which need a lot of VFX, so digital made sense. Then you had the small-budget art films that chose digital for cost and convenience – digital cameras are smaller, lighter and easier to use.

Emerging technologies continue to push the boundaries of storytelling. Some say that technology has surpassed the viewer’s imagination, to a point where some of the images you see on screen aren’t “real” anymore. Films like Gemini Man and The Irishman rely heavily on digitally rendered images where you don’t capture live performances in-camera.

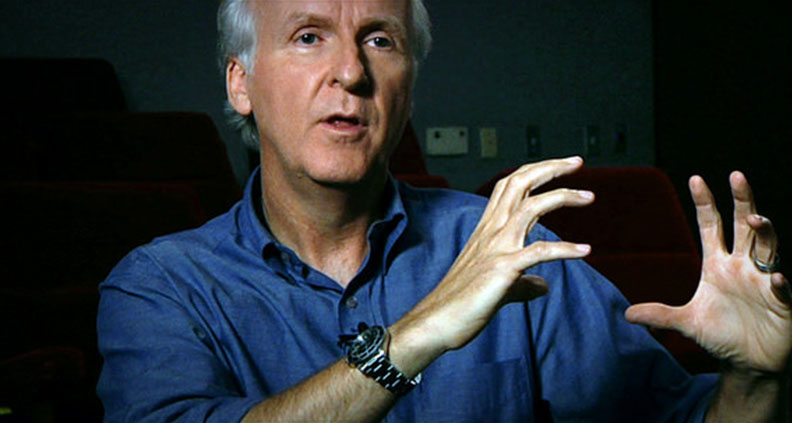

Kenneally: In the documentary, remember when James Cameron challenged: “When was it ever real?”? In the old days, you would use matte paintings, models or props to create the background – think spaceships in Star Wars. Now we can do so much more with green screens and VFX. So it’s always been hard to tell reality from manipulated reality in cinema.

The way we consume stories has changed a lot in the past few years – Quibi now makes episodic series that are 7-10 minutes long. How has digital changed filmmaking and what we see on the screen? In your opinion, has it changed the kind of stories we get to see now?

Kenneally: Already Gone was shot on digital, but is a very analog era film – it’s a coming-of-age road trip drama. There are always different technologies that help us tell stories, but the DNA of a story isn’t going to change depending on the tools you use. Many movies now rely heavily on VFX to create the sensations that transport us into a fantastical world that cannot be captured or replicated in reality. You can’t strap a 35mm camera onto the helmet of a mountain biker going over a jump – think of how they made Free Solo. As technology keeps changing, it also gives you more options to tell the story in ways that you couldn’t before.

The 5-part DVD expansion series has been even more illuminating. Would you ever consider doing a follow up to the doc to talk about how things have changed since 2012?

Kenneally: It would be great to be able to that some day! Revisiting this now brings me back to how much fun it was when we made the film.

Side by Side is available on streaming platforms and the Side by Side Extra: Volumes 1-5 are available on DVD. Find Chris @kenneally8 on Instagram and check out the documentary’s Facebook page.

Film Independent promotes unique independent voices by helping filmmakers create and advance new work. To become a Member of Film Independent, just click here. To support us with a donation, click here.