CASE STUDY: The Making of ‘Green is Gold’

Every other week on the blog, we dig into the archives from Film Independent Education and examine, in detail, one film’s production journey. Our hope is that filmmakers will take lessons from these stories to apply to their own projects. Good luck!

***

This week: After a teenage boy’s father goes to prison, he is forced to live with his older brother who has a compromising trade.

GREEN IS GOLD

Type: Narrative Feature

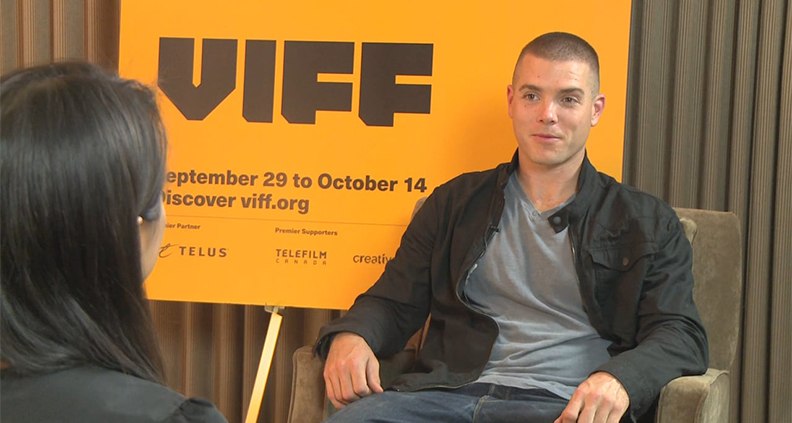

Writer/Director: Ryon Baxter

Producers: Anthony Burns

Budget: $110,000

Financing: Self-financed/Loans

Production: 30 days, July-August, 2013; + pickups in July 2015

Shooting Format: RED Epic

Screening Format: DCP

World Premiere: LA Film Festival 2016

Distributor: Samuel Goldwyn Films

Website: www.samuelgoldwynfilms.com/green-is-gold/

DEVELOPMENT AND FINANCING

In 2008, writer/director Ryon Baxter was preparing to leave for film school in Vancouver when he was arrested for a non-violent offense related to medical marijuana—and his plans for the future were put on hold. Baxter used all of his resources to fight the charges for two years before accepting a plea bargain and serving two months in jail in 2010. Film school may have been off the table for the moment, but a friendship with his cellmate would be the inspiration for Green Is Gold.

“He had this kind of northern California outlaw lifestyle,” Baxter remembers, “and I ended up basing this character on him—and then taking a lot of creative license.” His sentence served, Baxter did return to film school in 2010 with an outline for the film, and proceeded to write and rewrite a script over the next three years. “I knew that I wanted this to be my first feature film. I knew that I wanted to shoot a coming-of-age crime drama that was very character-driven and that took place in northern California against the backdrop of the cannabis industry. And I knew that I wanted to handle it as authentically as possible.”

For Baxter, the story felt personal, and became more so when he cast his youngest brother to star in the film. Just like the character played by Jimmy Baxter, Ryon and his brother had a father in prison at the time of production, and the filmmaker admits that the story provided a sort of catharsis for him personally, though the dynamics among the onscreen family members were entirely fictional.

“When I was in film school, I had all these grandiose ideas about who could play what,” Baxter admits, reflecting on the casting process. “But then the reality of trying to make it without any representation or money or any kind of body of work—it’s really challenging to cast people if you’re new.” Eventually, he began to accept that he’d need to work with unknowns. Baxter cast brother Jimmy in a short film that would serve as a proof of concept for the feature, and his decision reinforced the idea that he might be able to do without big names.

To cover production, Baxter borrowed $25,000 from a friend, which he paid back over the following year and a half. “You can raise money much more easily if you have something, rather than nothing,” the filmmaker says. Though he knew the initial outlay would only be enough to get him through production, it also made raising the funds he would need for post seem possible.

Securing locations would be another hurdle. In order to nail down a house that he could control completely, Baxter moved into a rental where he planned to shoot. (He was transparent with the landlord, who agreed to have his property filmed.) The filmmaker also did an enormous amount of research—consulting multiple entertainment lawyers—into the legal parameters of filming large numbers of marijuana plants, which are central to the plot. Without getting too specific, he attributes the incredibly realistic plants featured in the film to “really good art direction.”

PRODUCTION

Green Is Gold shot for 28 days in northern California the summer of 2013. Driven to make the project a reality, Baxter had constructed a bare-bones budget that would cover only the essentials. Craft services had been sacrificed and his crew consisted of four film school friends who either volunteered or worked on a barter system; one of the film’s two DPs traded each day of work on Green Is Gold for one day using Baxter’s RED Epic package on his own project. Another of Baxter’s younger brothers produced the film, for minimal compensation, and day players volunteered their time (though Baxter eventually compensated them once the film got distribution.)

After the end of principal photography, the team shot a few pickups that had been bumped from the schedule, but waited a good deal longer to shoot the final scene, that takes place more than a year after the main events of the film. “We needed time for Jimmy’s hair to grow out. We needed him to look older,” Baxter explains of the decision to wait an entire year to shoot pickups in the rental house, in which the director was still living.

“I didn’t have the money or the energy to finish [the film] in a timely fashion, because I was working to pay off the debt I’d acquired while making it.” It was a blow when his landlord hiked the rent nearly 50%, perhaps hoping to cash in some Hollywood money. Baxter stayed long enough to finish his reshoots before moving out.

FESTIVAL PREPARATION AND STRATEGY

While paying off his initial production loan, Baxter managed to create an assembly edit, but was dissatisfied with the sound and color in particular. “It was pretty unbearable to watch, and I considered chalking it up to a learning experience and moving on to another project.”

With no guarantees that additional work and debt would actually move the film forward, Baxter actually contemplated walking away. It was his team that inspired him to push forward. “Everyone had put so much into it—it was such a small production that anyone who had anything to do with it had such an integral part in the film. Everybody was doing four different jobs. Everybody wanted to see it through, and I wanted that too,” he explains of the choice to take out an additional loan to cover post.

But Baxter felt lost about next steps, and consulted longtime friend and fellow filmmaker Anthony Burns, who was living in Sonoma while adapting a book about the Grateful Dead. Burns agreed to come aboard as producer and Baxter credits him with driving the film to the finish line. Through Burns, Baxter met Sean McKittrick and Ray Mansfield of QC Entertainment; Baxter and Burns screened the film for the pair, who signed on as sales agents and executive producers.

Baxter submitted to only a handful of festivals, including Sundance, SXSW and—on the very last day of open submissions—the LA Film Festival. LAFF accepted the film, on the condition that it host the world premiere, and Baxter was thrilled. Considering the city’s love of cannabis, it seemed only appropriate.

THE SALE

LAFF was an extraordinary experience for Baxter, who relished the opportunity to connect with other filmmakers. QC had connected the director with publicist Michele Robertson, and when the two met over lunch, Baxter was inspired to learn that Robertson’s first PR gig had been on Edward Burns’s The Brothers McMullen—one of the movies that had inspired him to become a filmmaker.

Green Is Gold was well received at LAFF, and QC Entertainment sent the film to numerous distributors following the premiere. Roughly two months later, an offer came in from Samuel Goldwyn Films, which had lost an acquisition and now needed to fill an open slot. The distributor paid $25,000 for North American rights.

Baxter had just 30 days to complete a hefty list of deliverables—and had only Burns to share the load. Music licensing fees came to $12,000; legal fees were another $10,000; and a new sound mix would cost $7,000. (Though Baxter had finished sound and color before the premiere, they didn’t meet the distributor’s quality control standards and had to be redone.) Since the film now had distribution, Baxter also felt obligated to compensate cast and crew who had worked for nothing.

“It wasn’t about the money to me. I just wanted everyone to feel good about the project,” he says. All told, delivering the film would cost Baxter roughly $15,000 more than the sale price of the project, and for a third time, he had to borrow additional funds.

At McKittrick and Mansfield’s suggestion, Goldwyn agreed to represent the film for foreign sales, and has since sold worldwide streaming rights to Netflix.

THE RELEASE

Green is Gold had a limited release at one Los Angeles theater on October 7, 2016, and on VOD on December 6 of the same year. It was also briefly available through Redbox. Not surprisingly, Baxter has yet to receive VOD numbers. Though he’s only recouped roughly $30,000 of his considerable investment, he’s been gratified to see the film appearing in unexpected places—he spotted it on a Virgin America flight—and to know that it continues to be available to an audience.

ADVICE FROM THE FILMMAKER

“Make sure you get all the contracts done ahead of time,” Baxter advises. “Be on top of the releases, licensing and contracts before you step foot on set so there’s no last-minute leveraging [when the film gets distribution].

“And work with people you love and trust.”

Learn more by visiting our library of case studies for additional resources. Film Independent promotes unique independent voices by helping filmmakers create and advance new work. To support our work with a donation, please click here.

To become a Member of Film Independent, just click here. New Members who join this week will receive 15% off the cost to join or renew. To support us with a donation, click here.