A Brief History of the Film Independent Spirit Awards, Part One: 1986-2000

The 58th annual Academy Awards–presented by ABC on March 24, 1986 and celebrating the (alleged) best films of the movie year 1985–were watched by approximately 37.8 million television viewers. The Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, where the ceremony was hosted by the odd-throuple pairing of Alan Alda, Jane Fonda and Robin Williams. The evening’s big winner? Out of Africa, now regarded as one of the most turgid Best Picture winners of all time.

Two days earlier, March 22, a very different awards ceremony had taken place across town. The venue this time had been the rear ballroom of 385 North–a La Cienega restaurant. Here, amid a constellation of potted ficus trees and gold lamé drapes, unfurled the very first edition of the Film Independent Spirit Awards, hosted with casual luncheon hunkiness by Jagged Edge actor Peter Coyote.

The big winners? Martin Scorsese’s subversive black comedy After Hours (Best Feature, Best Director) and the Coen Brothers visually arresting neo-noir debut Blood Simple (Best Director, shared with Scorsese, Best Actor.) The most notable fashion moment? Inarguably cinematographer Haskell Wexler’s leather necktie.

As you already well know, the organization that would in later years be known as Film Independent first coalesced a few years earlier and was by 1986 up and running as IFP West. And since its inception, a regular part of the IFP West calendar had been its annual “FiNDIE” fundraising luncheon, which in its third year debuted a new awards element, the brainchild of then-IFP president Jeanne Lucas.

Introducing that debut ceremony, Lucas said: “This is really the first time, I think, that independent filmmakers have gathered together to celebrate the achievements of their own.” It would certainly prove the most enduring, as would the statuette designed by Carol Bosselman to serve as the awards’ prize and icon, the same design still used today. As Coyote explained in 1986: “The top features an abstract bird representing us–the independent filmmaker. It’s taking flight from a classical column, which represents the Hollywood establishment. And clutched in its talon is the ubiquitous shoe string.” In fact, shoestring imagery (shoestring budgets, get it?) would feature prominently in IFP West and Spirit Award iconography for years.

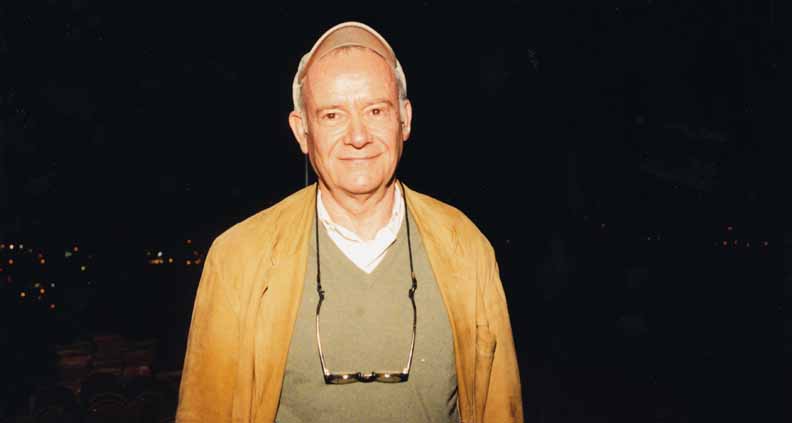

By its second year, the Spirit Awards had discovered a regular host in Buck Henry. A New Hollywood screenwriter and director best known for writing The Graduate and co-directing Heaven Can Wait with Warren Beatty as well as frequent hosting gigs on Saturday Night Live, Henry would host the Spirit Awards for eight consecutive years.

During this nascent era, the show moved out of the back of 385 North and bounced around a hotel ballrooms all across the city (The Hollywood Roosevelt, Beverly Hilton, etc.) before finding itself, somewhat bewilderingly, inside a large circus tent for its 1991 edition, erected in the parking lot of Raleigh Studios in Hollywood, where Martha Coolidge’s Rambling Rose bested fellow Best Feature nominees Homicide, My Own Private Idaho and Hangin’ with the Homeboys.

Somehow, the venue made sense. Filmmakers, after all, are nothing if not the tightrope-walkers, gregarious megaphone-barkers and cruelly exploited, fez-wearing elephants of the entertainment industry. The next year, 1992, a secondary component to the Spirit Awards’ physical identity was added when the tent moved to the beach in Santa Monica–the show literally placing itself as far away from the center of Hollywood as was possible before actively drowning its constituents or triggering a stingray frenzy. It was a potent metaphor, one that simultaneously supported the ceremony’s growing reputation as a casual, often irreverent hang. Once established, the Spirit Awards would only occasionally deviate from hosting its festivities on the beach, for better or worse.

A review of nominees from the Film Independent Spirit Awards earliest years–its 1980s era, into the early 1990s–reveals titles both indelible and influential (The Player! Bad Leitenant! Sex, Lies, and Videotape!) as well as obscure and essentially forgotten (Shag! Queens Logic! The Ballad of Little Jo!)–many of the latter aren’t available on streaming, and perhaps never even made the leap to DVD or Blu-Ray, victims of the purge that occurs at the margins of media any time a new consumer format is introduced. But! Through the Spirit Awards, these titles remain a part of the artistic record, honored in ways however fleeting or brief that preserve the possibility for rediscovery.

As gray suits and hair metal gave way to grunge music and heroin chic, the Independent Spirit Awards were fully established and poised to meet the cultural moment–a moment the awards were both in sync with and partially defined. Chief among them, Quentin Tarantino and Pulp Fiction’s triumph at the 1995 ceremony, his celebrity-auteur status signaled by a bright red suit jacket–practically a bullfighter’s cape, enticing the salivating Hollywood toro to charge him at his end of the amphitheater.

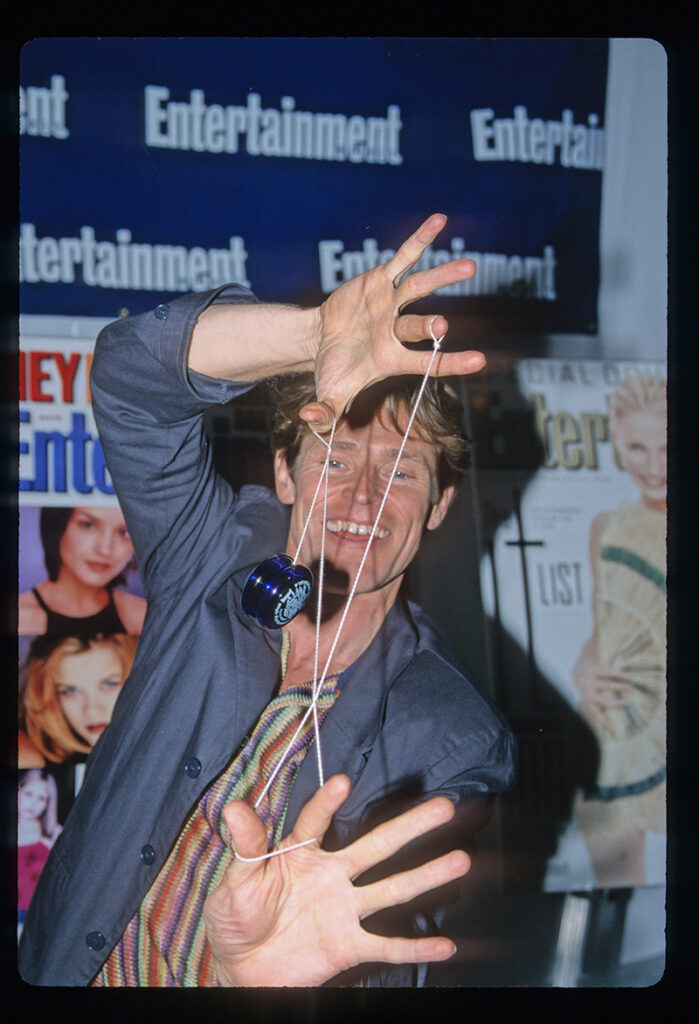

That 10-year anniversary ceremony was hosted by The Usual Suspect’s Kevin Pollak, taking over from the previous year’s host Samuel L. Jackson. In ‘95, Jackson won the Spirit Awards’ Best Male Lead trophy for Pulp Fiction’s Jules (Jackson was nominated for Best Supporting Actor at the Oscars for the same role that year, and lost.) In addition to Jackson and Pollak, the late-’90s Spirit Awards host roster included a wide range of emcees, including Jennifer Tilly, Queen Latifa and John Tuturro.

But even as independent film erupted into the mainstream during the mid-1990s, the Independent Spirit Awards remained future-focused, using categories earmarked for first-time writers, directors and breakthrough performances to spotlight the next generation of talent via some of their earliest projects. Here, you had Kelly Reichardt’s River of Grass, a 1996 Best First Screenplay nominee. You had Paul Thomas Anderson’s Hard Eight, nominated for Best First Feature in 1998. There was Tamra Jenkins’ Slums of Beverly Hills, Miguel Arteta’s Star Maps and Darren Aronofsky’s Pi. Plus debut performance nominations for Jeffrey Wright (Basquiat), Rose McGowan (The Doom Generation) and Rene Zellweger (Love and a .45) among others.

In the 2000s, the Spirit Awards–soon to officially be known as the Film Independent Spirit Awards, in order to make its relationship to the organization that produced it (and for which its primary purpose was to serve as annual fundraiser) more clear–would form strategic media partnerships that would make its reach even more pronounced, while at the same time refining its identity within the awards-o-sphere as colorful and comedy-oriented. But! You’ll have to wait for Part Two to learn about all of that…

To see all this year’s nominees, click here. Remember to tune in to the 40th Film Independent Spirit Awards on Saturday, February 22, 2025, which will be helmed by returning host and Saturday Night Live alum Aidy Bryant. The show, taking place at the beach in Santa Monica, will be streamed live on the IMDb and Film Independent YouTube channels, and across our social platforms.

Film Independent promotes unique independent voices by helping filmmakers create and advance new work. To support us with a donation, click here.

More Film Independent…

A former member of the Film Independent staff, Matt Warren is a Utah-raised, Louisville-based writer, director and producer whose most recent work is the feature Delicate Arch, premiering February 11 2025 on Screambox and available for rental on all platforms. He has made numerous scripted and unscripted web series, and has worked as a film critic, entertainment journalist, humorist, editor, graphic designer and videographer. His favorite movie is Repo Man, directed by Alex Cox.