Know The Score: The Psychology of Film Music

Each month in Know the Score writer and composer Olajide Paris will step out of the scoring stage and explore, in detail, some important aspect of movie music. After all, film is as much about what you hear as what you can see.

***

Why do we have the emotional associations with certain musical elements that we do?

For decades film composers have relied on specific combinations of instruments to represent different moods. When you hear a high melody played in a major key, you immediately think of adventure or heroism. Picture any John Williams fanfare—like Indiana Jones, Superman or the Olympics theme. Meanwhile, the bouncing woodwind phrases ubiquitous in comedy films likely fills you with an immediate sense of farce.

For the most part composers depend on these associations to define specific moods in the creation of their original film scores. But why do we have the associations that we do with certain instruments or genres?

It’s an important question, the answer to which is key to understanding the contextual considerations that need to be made when approaching a score. A comprehensive lesson on the history of music or music theory is well outside of the scope of this article, but I’ll do my best to give you a broad strokes overview of a few essential concepts.

HOW WE GOT HERE

The last 800 years of music can be broken up into a few distinct time periods during which a single style of music was dominant:

- Medieval (c.1150 – c.1400)

- Renaissance (c.1400 – c.1600)

- Baroque (c.1600 – c.1750)

- Classical (c.1750 – c.1830)

- Early Romantic (c.1830 – c.1860)

- Late Romantic (c.1860 – c.1920)

- Post ‘Great War’ Years (c.1920 – Present)

Arguably all of these epochs contributed to the evolution of music as we know it. But the rules of what we consider to be Western music were more or less established during the Baroque Period, further developed in the Romantic and Late Romantic Period and subsequently defecated upon in our current Postmodern, Postwar era.

Great—but how does this all relate to the psychology of film music? I’m getting there. But before I can talk about that, I need to cover a few basics. On the simplest level, what we think of as being “happy” or “sad” music was more or less established in the Baroque period. In Western culture, we think of chords or melodies that are “major” as being happy and chords or melodies that are “minor” as being sad, somber, grave, etc.

Examples of film themes in a minor key are: The Godfather theme, The Imperial March (aka Darth Vader’s theme) from Star Wars, the Harry Potter theme, the Kill Bill theme, etc. Examples of film music in a major key are: The Indiana Jones theme, Superman theme, Magnificent Seven theme. The list goes on.

Both major and minor sounds are thought of as being relatively “pleasing” to the ear. What isn’t considered to be pleasing, however, is dissonance: the combinations of notes that produce sounds Westerners think of as jarring or unsettling. Some good examples of dissonance in film music are the shower scene in Psycho and the theme for Jaws.

LET’S GET ROMANTIC

The lion’s share of the symphonic music borrowed by film composers comes from the late Romantic period and beyond. Here’s why: while earlier epochs of music were focused on rigid forms and rules; it was during the Romantic period that music became more colorful and expressive.

Composers like Wagner and Rachmaninoff provided a basic vocabulary for film music that would would persist in Hollywood until the end of the late 1950s. Late Romantic composers wrote “programmatically”—they were explicitly setting out to tell stories and evoke specific moods using carefully chosen instrumentation, harmony and melodies. What we now associate with as heroism (see Richard Strauss “A Hero’s Life”), tragedy (see Rachmaninoff “Isle Of the Dead”), romance (see “Wagner Tristan And Isolde”), etc. were all tropes established in the concert music of the late Romantic period.

Film music pioneers like Franz Waxman, Enrich Korngold and Max Steiner all came from the concert music world and leveraged these associations to form the foundation for film music that composers would continue to follow—and develop—for decades.

We’ve established that certain note combinations are meant to evoke specific moods and that certain instruments have become associated with specific scenarios or emotions. But how music functions on our psychology to achieve a specific dramatic effect by playing runs lot deeper than that…

HOW MUSIC WORKS, WHEN IT WORKS

When a score is working well in a film, it does a few things:

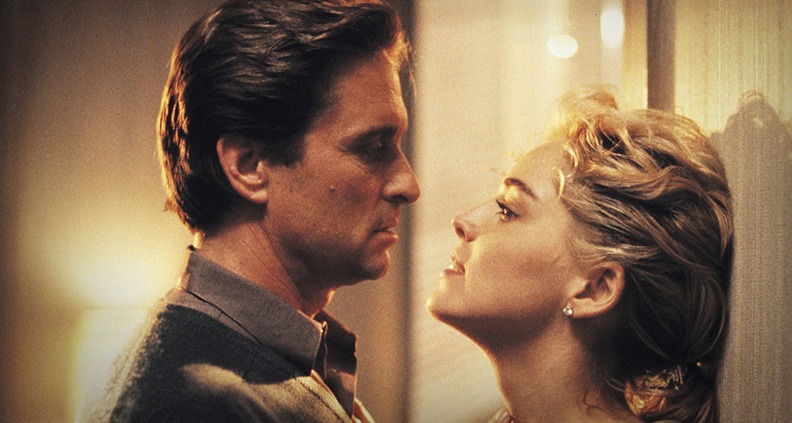

It communicates that which is unspoken. An effective score communicates a character’s mental state in ways that transcend the limitations of speech. Jerry Goldsmith’s score for Basic Instinct very effectively brings out the conflict that Detective Curran (Michael Douglas) is struggling with throughout the film. The score development reflects that of the main character. As Curran goes further and further off the rails, so does the theme become contorted and progressively skewed until a final discordant climax is reached. While it’s obvious without music that the character is struggling, the dissonant string swells used throughout the film help remind us of his conflict.

It tells us the “mood.” One of my favorite soundtracks of all time is Philip Glass’s score to the documentary Powaqqatsi. Despite a complete lack of dialogue in the film, the music along with skillful editing help tell a dramatic and cohesive story of the dangers of industrialized life and its impact on the earth and society as a whole.

It foreshadows. The ominous brass stabs in the theme to Bernard Herrmann’s score in Psycho belie the antagonist’s initially charismatic introduction, communicating to us early on what we know by the end of the film: “He’s a monster!”

It tells us what the world sounds like. A good score provides a feeling of time and space by telling us what the world sounds like. One of the questions a filmmaker has to ask themselves is “what does the world sound of this film sound like?” Meaning: “what is the musical aesthetic that coexists with and supports the aesthetic of the film?” What does the world around these characters sound like, and what instrumentation and treatment best underscores their emotions an inner dialogue?

While there are no hard and fast rules about what music is appropriate for what films, there are many examples—from the thousands of films—that we can draw from.

Take the period costume drama, for example. More often than not, the music in these films is evocative of the music that would’ve been in vogue during whatever period of time the film is about. It evokes what the world would have sounded like to the characters in those films.

WHAT’S YOUR APPROACH?

Depending on the tastes of the composer and director, scores may range from being on-the-nose-accurate—take Ludovic Bource’s score for the The Artist; in other cases, a score may simply evoke the spirit or mood of a period, taking some creative liberties along the way—such as Alexandre Desplat’s score for The King’s Speech, which paints a musical picture of of stateliness and nobility without being a musical caricature of a particular epoch.

On the other hand, Hans Zimmer’s score for Dunkirk eschews any traditional approach, opting for a sound-design-heavy avant-garde sonic palette that evokes the characters’ emotions, filtered through through the ears of of a modern audience—drawing a musical vernacular that would have been alien to the characters in the film, yet is crystal clear to a modern audience. The intense, persistently rising shepard tones used throughout the film, while not historically accurate, are incredibly effective in musically illustrating the feelings of fear and panic that the soldiers at war are experiencing.

Regardless of the genre, the challenge of the composer and the director is to decide whether to abide by the established conventions and maintain the status quo or go against the grain and surprise the audience. Whatever strategy is put use the composer will have the common challenge of manipulating the audience’s emotions in a way that draws them into the story and deepens their connection to the characters.

Olajide Paris is an American composer and producer based in the Republic of Georgia, where he produces soundtracks for clients around the world. He’s given lectures on the subject of film music at Los Angeles City College, Tbilisi Conservatory, Georgian-Irish Film Festival, Cinedoc Film Festival and the Georgian National Film Center. Check out his website here.

Learn how to become a Member of Film Independent by visiting our website, and click here to subscribe to our YouTube channel. Also, why not be our friend on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram?