CASE STUDY: The Making of ‘K-Town‘92’

Every other week on the blog, we dig into the archives from Film Independent Education and examine, in detail, one film’s production journey. Our hope is that filmmakers will take lessons from these stories to apply to their own projects. Good luck!

***

This week: K-Town’92 is an online interactive documentary directed by Grace Lee that invites you to explore the 1992 LA riots, uprising, and civil unrest through the untold stories and perspectives of greater Koreatown.

K-TOWN’92

Type: Interactive Documentary

Director: Grace Lee

Producers: Eurie Chung, Grace Lee

Budget: $110,000

Financing: Grants

Production: 4 months; January-April, 2017

Shooting Format: HD 1080p video

World Premiere: Online, April 2017

Website: www.ktown92.com

DEVELOPMENT AND FINANCING

Director Grace Lee was a recent college graduate living in Seoul, Korea when the LA riots broke out in the spring of 1992. Growing up in the American Midwest, Lee had hardly seen Asian Americans represented on TV at all. Now she was halfway across the world, watching Korean Americans at the center of a deeply disturbing news story.

“All of a sudden there were these images of Koreatown in LA basically burning to the ground, with stark images of Korean immigrants either sobbing over their torched businesses or wielding guns to protect them from looting,” she remembers. At the time, she tried to piece together the truth of what was happening through media coverage that didn’t help much to clarify the situation—and often inflamed existing racial tensions.

Having lived in LA for the past 20 years, Lee has since come to know Koreatown as an incredibly diverse and dynamic community—calling it home for the past eight years. As the 25th anniversary of the uprising approached, she and producer Eurie Chung grew concerned that the Korean experience would again be misrepresented in the media. With a spate of documentaries on the subject already in the works, the two decided to take a different approach.

“We wanted to highlight the stories that would challenge these familiar problematic images of the Latino looter, the angry Black protestor or the gun-wielding Korean, and offer up a different perspective. And the idea that we could just do it and put it out on the Internet was very appealing,” says Lee.

In October 2016, Lee and Chung attended the POV Digital Lab, a weekend media incubator for digital storytelling. “We wanted whatever experience we created to challenge the existing narrative of that period of time, and to go beyond the constraints of a traditional documentary,” Chung explains.

As neither Lee nor Chung had any experience in the digital world, they worked with both a Programmer and a “User-Experience” designer to craft a vision for how their narrative might function on a website. The learning curve was steep, but the project won the Participant’s Choice prize at the Digital Lab, which the team took as recognition of their mission—not just to recount familiar events, but to actively question who gets to tell the story.

Following the Lab, the pair consulted with several web developers to nail their concept down, selecting Folder Studio as their design and web development partner. As the creative components of the project came together, they enlisted Executive Producer Kathryn Lo to help seek out potential partners and funders. But with a tight timeframe necessitated by the upcoming anniversary, they were off-cycle for a number of grants and foundations that might have been a good fit.

Leveraging relationships they already had, they secured first funds from the Center for Asian American Media (CAAM). With enough in the coffers to begin shooting, the team focused on creating a prototype for the site that would make the idea for the site more tangible to help raise more funds. Ultimately, the prototype was crucial in securing grants from California Humanities and Ford Foundation Just Films.

In budgeting for the project, the team sought out friends who had worked in the digital space for advice on the cost of the skilled technical labor they’d need. Former collaborators agreed to work at discounted rates to capture some of the early footage, and Lee and Chung developed a partnership with Visual Communications, a support organization for Asian-American filmmakers and media artists. Lee knew that VC had an extensive archive of footage from the 1992 uprising, and the organization agreed to allow the filmmakers to use it for the project.

PRODUCTION

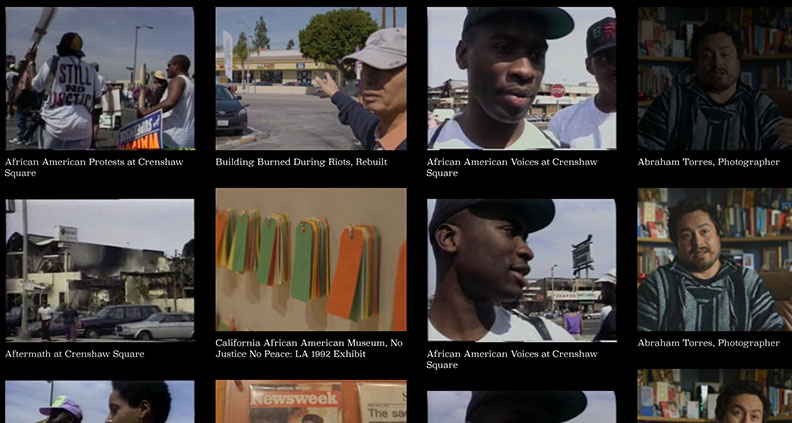

Lee began shooting interviews in January of 2017. To find subjects, she and Chung worked with several consulting producers who helped to bring in a diversity of perspectives and viewpoints. The filmmakers wanted to make sure that they were telling the stories of a broad cross-section of people who had been in some way affected by the uprising.

“We didn’t want any one story to dominate. We wanted it to be—similar to Koreatown—a place where lots of different people and stories would intersect,” Lee explains. They interviewed African Americans, Latinos and Muslim Americans, as well as Asian Americans, and partnered with the Koreatown Immigrant Workers’ Alliance and the Community Coalition in South LA. During pre-production, the filmmakers used a Google survey to put out an open call for home video footage and stories, but found word of mouth was a more effective tool for sourcing potential interviewees.

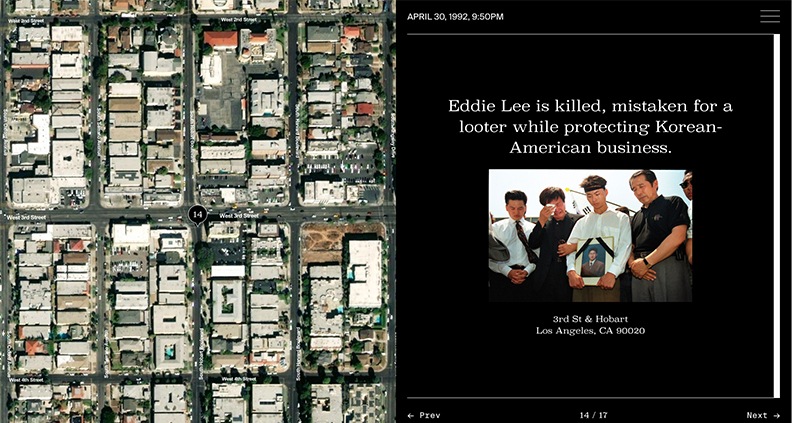

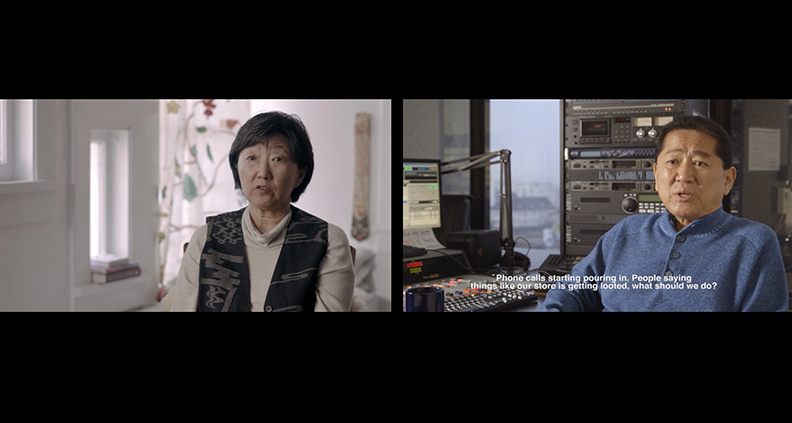

“We wanted different types of people AND footage in conversation with each other,” Lee says. Working with VC’s archival footage of the events of 1992, interviews she shot in early 2017 of a diverse group of Angelenos who had experienced the uprising and B-roll of Koreatown from both 1992 and 2017, Folder Studio helped Lee and Chung conceive a randomized user experience through which visitors to the site would be led from one piece of footage to another.

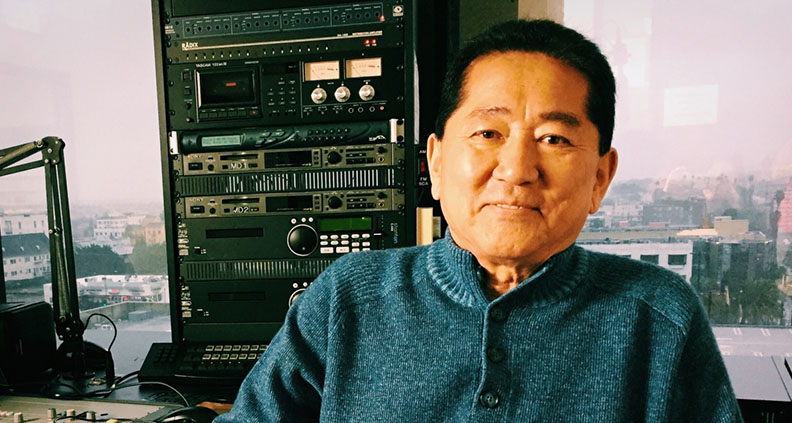

They created a tagging system that categorized footage with multiple key words, allowing the site to generate additional clips based on the ones a user had already viewed. The tag, “Koreatown,” for example, might lead from an interview with an African American man they interviewed at a tennis court reminiscing about the summer of 1992, to period news footage of looting, to a correspondent from Radio Korea remembering his experience of covering the story.

Chung credits the project’s design studio/development team with recognizing that the goal was a cinematic experience, and with crafting a site that allowed viewers to sit down and watch the narrative unfold. Visitors to the site have the option to begin with one of a handful of videos, but each journey through the material might take an entirely new trajectory.

Unlike a traditional documentary, K-Town’92 has no definitive ending. There are currently more than 1,700 pieces of footage available on the site, and Chung and Lee will continue to add new pieces to the site.

LAUNCH PREPARATION AND STRATEGY

In preparation for the site’s launch, the filmmakers approached different digital distributors, but most were concerned about the compressed timeline. Nonetheless, POV offered to support the project with some limited marketing, and Lee and Chung began to stitch together a short film documentary, K-Town ’92 Reporters—which explores the stories of three street reporters of color at the Los Angeles Times who were charged with covering the civil unrest—to accompany the site and build an audience.

With the anniversary generating so much discussion in media, the filmmakers found it was possible to get the word out through social media, panel discussions and community events. They also engaged Impact Media Partners to handle publicity.

THE RELEASE

K-Town ‘92 went live online during the last week of April, 2017. That same weekend, the project’s release was marked with several events at VC’s LA Asian Pacific Film Festival and conferences at USC and UCLA as well as the Smithsonian Museum of African American History. K-Town ’92 Reporters premiered on PBS’s World Channel, where it continues to screen.

As they continue to watch the site evolve, Lee and Chung have begun to consider its educational use; the site has already been used as a teaching tool in university classrooms, and the filmmakers look forward to finding more ways to make it available to educators. Though it will require more fundraising, they also plan to provide Spanish and Korean-language subtitling to make the site more accessible to a wider audience.

The filmmakers take pride in the fact that the evolving archive they’ve created will live on, and hope it will provide a window into history for a growing audience. “You can always come back and have a new experience, ” Lee says. “As long as you have an internet connection.”

ADVICE FROM THE FILMMAKER

Chung advises filmmakers to be thoughtful in ensuring that their approach to their material represents their intentions. “Make sure your interaction [with the work] is really true to your goals,” she offers, recalling that their original plan for an interactive map with video links wouldn’t have provided nearly the disruptive viewing experience the site has achieved.

Lee adds that the process of questioning and shaping a project is vital to achieving something fresh and new, until “the power of the story really takes over and the experience, hopefully, is not so obvious.

Learn more by visiting our library of case studies for additional resources. Film Independent promotes unique independent voices by helping filmmakers create and advance new work. To support our work with a donation, please click here.

To become a Member of Film Independent, just click here. New Members who join this week will receive 15% off the cost to join or renew. To support us with a donation, click here.