Noah Baumbach Gives Us a Close-Read of ‘The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected)’

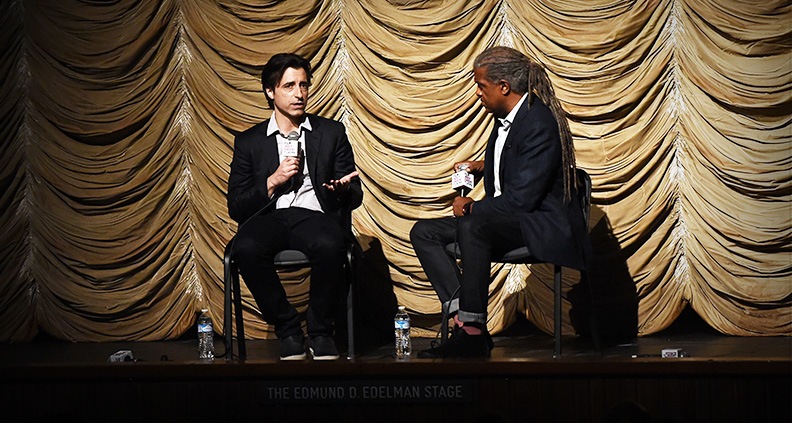

On October 12, Film Independent at LACMA held a Members-only screening of writer-director Noah Baumbach’s recently-released The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected) at LACMA’s Bing Theater. After the film, Baumbach joined Film Independent at LACMA curator Elvis Mitchell for an in-depth discussion delving into the veteran filmmaker’s creative process, use of subtext—even Randy Newman (the iconic singer-songwriter served as The Meyerowitz Stories’ composer, much to superfan Baumbach’s delight).

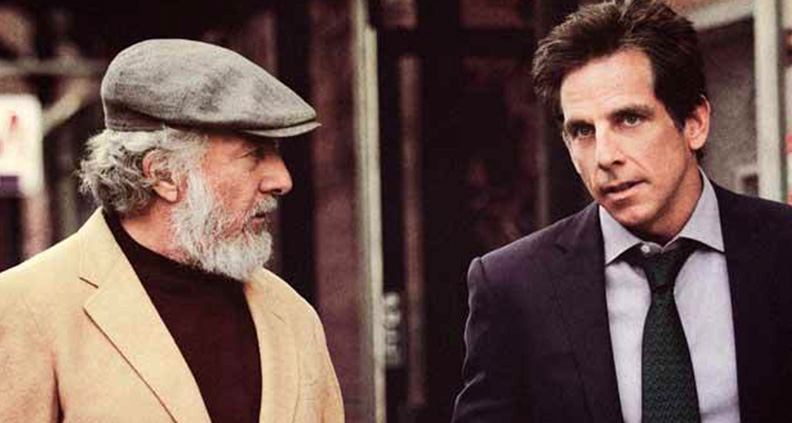

The Meyerowitz Stories addresses the dysfunctional—but relatable!—dynamics of a blended New York family, as three adult siblings (Ben Stiller, Adam Sandler and Elizabeth Marvel) struggle to negotiate their relationships in the face of the (possibly) impending death of their complicated, failed-sculptor patriarch (Dustin Hoffman). The result is a slew of emotional and witty moments that are well in line with the rest of Baumbach’s filmography. The movie is currently available to stream on Netflix, which acquired the film following its Cannes premiere.

Baumbach started writing the script in 2014—first meeting with Stiller, who plays the clan’s younger half-sibling Matthew, and Sandler, who plays neglected elder sibling Danny, the product of Hoffman’s character Harold’s first marriage. Baumbach was interested in exploring the clash of the personal and institutional, wanting to write something about the experience of seeing a loved one confined to a long hospital stay.

“I had this idea of separating the brothers,” said Baumbach, “and then I came up with the idea of what if this is a collection of stories by some made-up author who wrote them over the course of his career?” There it is! He said that the writing became easier after splitting the brothers up into their own vignettes, thereby further compartmentalizing the family.

Mitchell was interested in divisions within hospital bureaucracy, which can aggravate family dynamics, asking how crucial it was for him to write this aspect into the script. Baumbach had notes from his own hospital experiences, stating, “I was ready when I got there.” Regarding the somewhat lengthy narrative time-jumps in-between the film’s chapters, Baumbach said, “it’s not just what’s in the movie, but what gets left out.”

Mitchell noted that for Harold Meyerowitz, his sculptures seem dearer to him than his own children; in one scene he even cradles one as if it were an infant. “It was a family where art replaced religion in a way,” Baumbach said. “Art was valued above anything else.” Danny feels like a failure because of how his father has defined success—even though Sandler’s character is portrayed a remarkable parent. But Harold is unable to perceive that, nor can perceive his own successes, desiring greater praise.

Baumbach and Mitchell discussed the “Byron/Myron” scene—in which Hoffman’s Harold and Sandler’s Danny bond over a silly novelty song Danny wrote as a child—where Harold is notably less distant (even physically) from his family. Harold is enjoying himself here, though “it speaks to his limitations, what he can’t do,” said Baumbach.

“His kids are trying,” said Baumbach, “but he can’t see it because it doesn’t speak to what he needs—which is to be treated like some kind of special great artist.”

Mitchell asked why Baumbach is interested in narcissistic characters. Baumbach shared an anecdote from his friendship with the late Mike Nichols. Nichols said to him, “You realize how embarrassed we all are?” Added Baumbach, “Nobody else is thinking of [rival artist] LJ’s show as a reflection on Harold Meyerowitz, but Meyerowitz sees it as a grand humiliation,” he said—pointing out that most artists don’t achieve even the level of success the disgruntled Meyerowitz has attained, pursuing his artistic endeavors and enjoying a great teaching career.

Delving deeper into the discussion of how success is defined vs. failure in the Meyerowitz family, Baumbach spoke to buying into the characters’ own feelings of failure. “I wanted to demonstrate how this rewriting of history is happening in front of children all the time.” Although [they’re] adult children now, just like with any family certain mythologies are passed down. We all inherit these mythologies from our families, go out in the world and suddenly find ourselves realizing [that we] define success a certain way, and that [we] kind of have to unlearn those things.”

Now we arrive at dialogue! Baumbach said that Hoffman informed his own process by actually requesting line readings from the director. Getting the rhythm of the dialogue right significantly informed the character for Hoffman. “I loved working that way,” Baumbach told the audience. He added that in making movies, so much of the process involves perfecting the dialogue. “It’s a combination of technical [choices] and the magic that great actors have, they are able to make it both close to them and also this invented character.”

Randy Newman is crucial to the film. Before shooting began, Newman sent Baumbach a song he had written (overnight!) on piano, which became the film’s main theme. “It was a great gift, because it was also like seeing my movie before I shot the movie,” said Baumbach. “This is the music of the movie and I haven’t shot it yet.”

For this project, Baumbach was looking to embrace the “singer-songwriter voice” of Newman. “It happened to be the song ‘Old Man’—it felt like it was written for the movie.” So Newman went ahead and supervised the reediting of the song, specifically for the film.

Said Baumbach, “At the New York Film Festival, he [Randy Newman] came and I introduced him first, and then the cast, with Dustin Hoffman. What a great day, to get to work with those guys.”

The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Collected) is currently available on Netflix and in select theaters—check out the film’s Facebook for more information.

To see what’s coming up at Film Independent at LACMA, click here. And learn how to become a Member of Film Independent by clicking here. Not a Member of Film Independent yet? Become one today.