Art Meets Activism with #BlackLifeBlackProtest at the LA Film Fest

“How many people made it through the weekend without seeing what came out of McKinney, Texas?” Christine Acham, Associate Professor of Cinematic Arts at USC, asked the audience at the LA Film Fest’s #BlackLifeBlackProtest event two weeks ago. Everybody, of course, had seen the Texas pool party video. “That’s the power of social media, and the power of what we can do in terms of being both activists and filmmakers,” Acham said. “I really sort of have to thank God for the iPhone.”

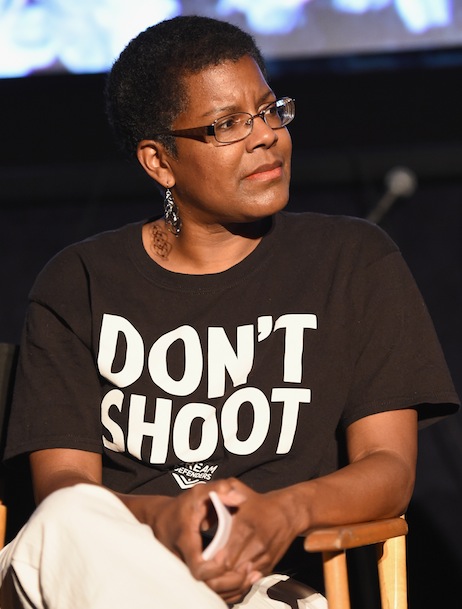

The event was part of the Festival’s Launch section, which puts the spotlight on storytelling in digital media, and it was split into two parts: first, a screening of seven short films dealing with the Black Lives Matter movement in the form of documentary, satire, drama and honest conversations about black identity. The second half of the event was a panel moderated by Acham and featuring actor Tony Okungbowa, author Tananarive Due and activists Ashley Yates and Damon Turner. Some of the filmmakers were in attendance and joined in the discussion.

The short films in the program were:

We Demand Justice for Renisha McBride, a documentary short by dream hampton that portrays the aftermath of the 2013 murder of Renisha McBride in Dearborn Heights, Michigan. Protesters call for the indictment of her killer and chant McBride’s name, imploring the viewer not to forget her.

#AmeriCAN, a short dramatic film directed by Nate Parker, also addresses the murders of innocent black teenagers by police. A police officer chases a group of teenagers who he believes robbed a convenience store. Shots are fired, and it ends with a bitterly ironic twist.

Wade in the Water: Movement Talk, a documentary short directed by Terrance Pitts, features congressman John Lewis, who recalls his own involvement in the Civil Rights Movement in the ’60s—and notes the similarities between his work then and the Black Lives Matter movement today.

Counter, a historical dramatic short directed by Project Involve Fellow Nicholas Bouier, portrays a protester in the segregated South stopping at a lunch counter before marching with Martin Luther King, Jr., and the tense dynamic between himself and the white waitress who is torn over whether or not she should serve him.

BlackCard, a satirical short directed by Pete Chatmon, imagines a world where African-Americans have “BlackCard” IDs, and an agency called the Interracial Affairs Commission enforces individuals’ commitment to their own black identity. If the IAC finds that you voted for Romney or bought kale at Whole Foods, you just might get your BlackCard revoked.

Protect and Serve, a satirical short directed by Jai Tiggett (who also curated the program), is about three police officers who are forced to wear body cameras. The officers range from being professional and productive to shamelessly racially profiling, planting drugs in victims’ pockets and making people (literally) tap dance for their lives.

Question Bridge: Black Males, directed by Chris Johnson and Hank Willis Thomas, is part of an ongoing transmedia project in which black men answer questions about their experience, and engage in a candid dialogue about their own diverse identities.

The activists and filmmakers’ discussion that followed focused on the importance of work like this as well as the difficulty of making it. Diversity of the black experience was a major topic in the ensuing discussion. “We’re complex, we’re nuanced and we’re diverse,” Pitts said; Acham agreed, “There is no monolithic blackness.” So why are the representations we see of it in popular media so unvaried? “The Caucasian community are free to play serial killers, mass murderers, maids, cops, whatever they want to be,” James Lopez, a studio executive and producer of AmeriCAN, said. “Sometimes I’ll read a script and I’ll struggle with, ‘is this responsible? What kind of image am I putting out there?’ But at some point, we have to be allowed to be whatever we want to be.”

The responsibility of the artist to portray black characters in an honest and productive way was a major topic of discussion. “I’m always aware of, ‘how am I depicting black masculinity in this piece?’—Even if it’s not a political piece,” sid Due, thinking of her 11-year-old son, who she knows is “the target [that] the police are looking for.” Okungbowa recalled an experience just a few weeks ago in Nigeria, where he heard a group of children using the n-word casually: “They are just quoting a lot of stereotypes that a lot of the films that are being put out are giving,” he said. “Images are so powerful. If, as a filmmaker, you want to do what you do with no social responsibility, that is your call—but it has a ripple effect.” Turner added: “Entertainment is one of America’s biggest exports to the rest of the world. Art for art’s sake is wack as hell.”

Achan pointed out that every single image of blackness—no matter how small or inconsequential to a film’s plot—is political, and it communicates something. “Art has to be political in this moment,” Yates said. She emphasized the value of artists communicating with each other and staying connected, and placed huge importance on being informed. “If you’re going to make political art, you should be connected to the politics,” she said. “We have to have people who are knowledgeable about what they’re actually making films about. Being black does not give you the inherent knowledge.”

Just a few days after the panel, the mass shooting at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston took nine more lives, reminding us all how enormously important this work is, and how far we still have to go. Black Lives Matter.

Mary Sollosi / Film Independent Blogger